How the intersectionality, ambiguity, and possibility of the liberal arts translates to interface

Research, strategy, creative direction, design. Made at Happy Cog, November 2017–April 2018. Information architecture and content strategy led by Lisa Maria Marquis.

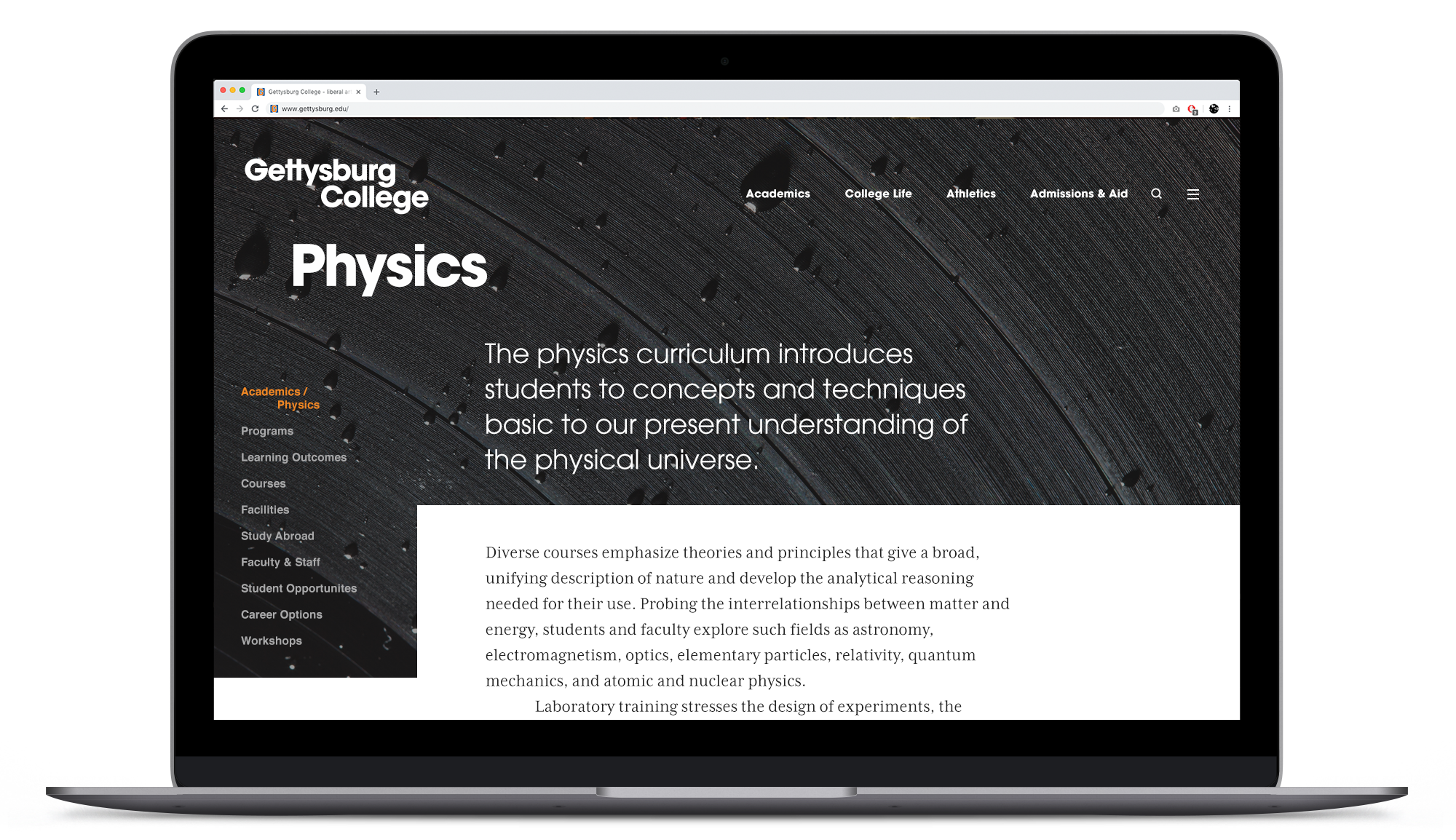

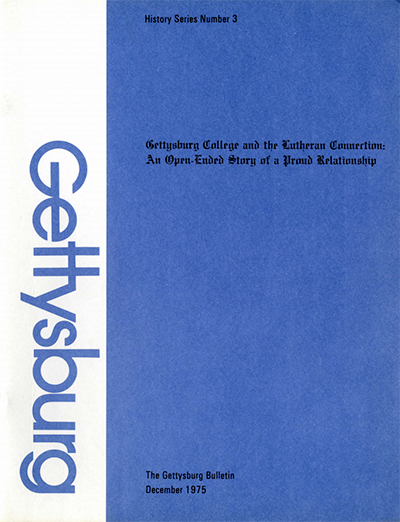

The refreshed identity livens up the brand while maintaining the visual hierarchy and relationships internal teams were comfortable using.

Designing an experience with the liberal arts in mind

The astronomical cost of college has become increasingly prohibitive to all but the most privileged. The blame for this has been laid at the feet of the colleges themselves, and not altogether by the political right, where being uneducated has been made out to be a kind of virtue, a synecdoche for uncomplicated honest living, but also by left-moving liberals, where the free-college movement has cast mainline institutions as villainous robber barons.

These characterizations bother me for reasons I won't get into much here, other than to occasionally point out both extremes are based on ideological grounds rather than historical fact, and unfairly diminish the federal government’s role in passing national debt onto individual students.

My job for Gettysburg wasn’t to do public relations anyway, either for college in general or the humanities in particular, whose enrollments nationwide have declined so sharply that some colleges have eliminated them altogether.

But this decline is just too hard to ignore.

Take University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, for instance, who dropped art, philosophy, language, history, but not graphic design, presumably because of its status as a trade, though without its antedisciplines it’s been so thoroughly denatured I have difficulty imagining the actual curriculum. Gone too are American studies, sociology, political science. Taking the changes as a whole you see Stevens kept only what was immediately serviceable to the market, eliminating liberal arts ambiguity for the non-branching paths of a trade school.

Other liberal arts colleges less interested in forsaking their belief systems to make enrollment goals have instead adopted marketing language around outcomes and career placement. Naturally part of convincing a student that your college is the one for them is giving these kinds of assurances.

![]()

Basing the design off 1970s materials had greater significance than just aesthetic: Reagan’s policies, namely financial deregulation and restrictions on federal funding for education, marks the beginning of higher education’s transformation from place of self-discovery to vocational bootcamp. Returning to Gettysburg’s 1970s look squared with the overall site strategy.

Still, I wouldn’t say many colleges fully embrace ambiguity. Southern Illinois University–Carbondale on the other hand has totally dissolved academic departments to streamline operations, cut costs, and eliminate “bureaucratic, artificial boundaries.” Insiders are dubious of its honesty, but at least on paper chancellor Carlo Montemagno’s plan reflects a core liberal arts belief in that a blended, unbounded education facilitates innovative interactions between disciplines.

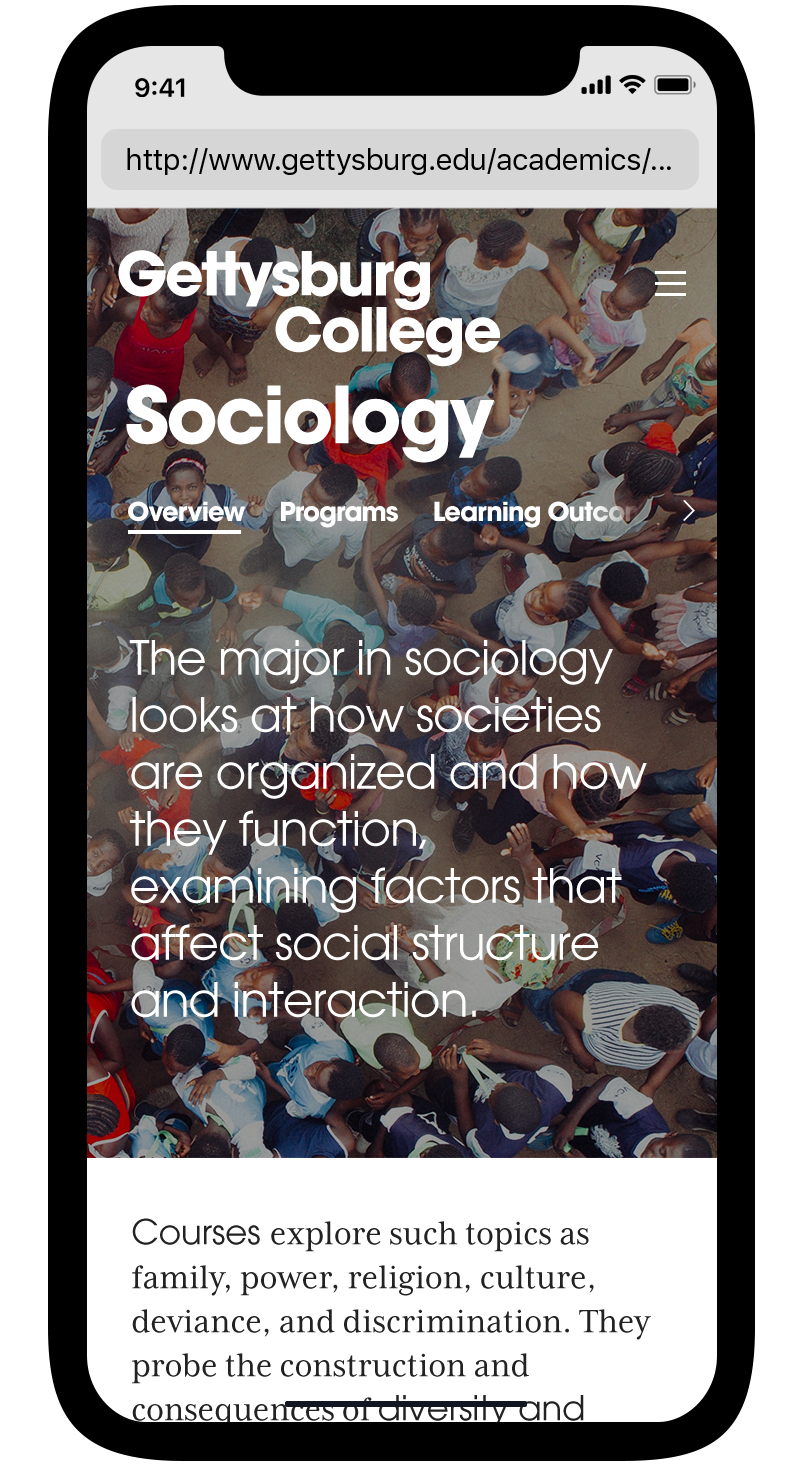

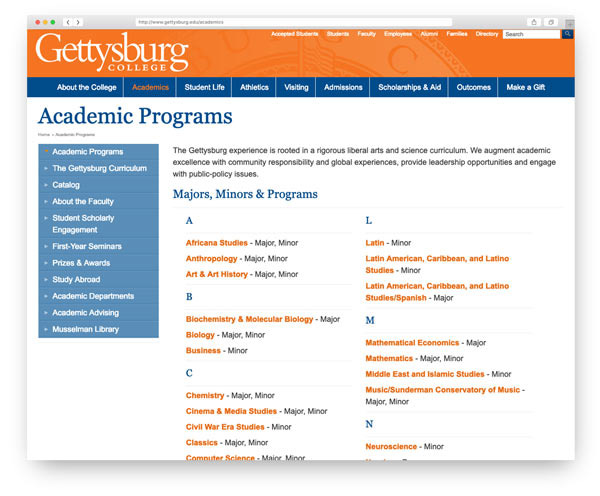

Interestingly when I met with Gettysburg they followed a similar model in spirit, organizing programs on the website strictly by alphabet and making use of departments only when administrative scaffolding couldn't be avoided. Eventually we learned the faculty’s reverence for this arrangement was out of deference to one another, since any other organizing principle inflicted a top to bottom ordering of importance, and all programs were, in theory, equally important. (I’m not blowing smoke, either. We proposed departmental organization as an option and several faculty members on one committee were, let’s say, vociferous in their dislike.)

![]() Less is a bore: The original, apolitical yet still deeply political academics landing page.

Less is a bore: The original, apolitical yet still deeply political academics landing page.

While noble, this presented a couple of unusual challenges. The first was that, being flat—fair is, I think, the better word—the College was ‘showing its underwear,’ exposing its political life on the website and thereby imposing a sort of featurelessness on the user which made certain parts of the site—arguably the most important sections—difficult to use and uninteresting to look at. (That old designerly saying, “if everything is important, then nothing is important,” doesn’t work in the reverse: When nothing is important….)

The bigger trouble, though, is how a design ethic like this can be taken. In the wrong setting deliberate non-design, already a contradiction in terms, is liable to come off less egalitarian and democratic than unimportant and uncared-for.

Recognizing that we saw two ways forward.

Either steer the College toward more traditional ways of web-thinking—which would contemporize the site, achieve basic parity with other schools, but perhaps go against their values—or take a cue from their own attempts, bushwhack our way through a jungle of unknowns, and conceive of a total experience, from brand to content model, based on their liberal arts epistemology.

These characterizations bother me for reasons I won't get into much here, other than to occasionally point out both extremes are based on ideological grounds rather than historical fact, and unfairly diminish the federal government’s role in passing national debt onto individual students.

My job for Gettysburg wasn’t to do public relations anyway, either for college in general or the humanities in particular, whose enrollments nationwide have declined so sharply that some colleges have eliminated them altogether.

But this decline is just too hard to ignore.

Take University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, for instance, who dropped art, philosophy, language, history, but not graphic design, presumably because of its status as a trade, though without its antedisciplines it’s been so thoroughly denatured I have difficulty imagining the actual curriculum. Gone too are American studies, sociology, political science. Taking the changes as a whole you see Stevens kept only what was immediately serviceable to the market, eliminating liberal arts ambiguity for the non-branching paths of a trade school.

Other liberal arts colleges less interested in forsaking their belief systems to make enrollment goals have instead adopted marketing language around outcomes and career placement. Naturally part of convincing a student that your college is the one for them is giving these kinds of assurances.

Basing the design off 1970s materials had greater significance than just aesthetic: Reagan’s policies, namely financial deregulation and restrictions on federal funding for education, marks the beginning of higher education’s transformation from place of self-discovery to vocational bootcamp. Returning to Gettysburg’s 1970s look squared with the overall site strategy.

Still, I wouldn’t say many colleges fully embrace ambiguity. Southern Illinois University–Carbondale on the other hand has totally dissolved academic departments to streamline operations, cut costs, and eliminate “bureaucratic, artificial boundaries.” Insiders are dubious of its honesty, but at least on paper chancellor Carlo Montemagno’s plan reflects a core liberal arts belief in that a blended, unbounded education facilitates innovative interactions between disciplines.

Interestingly when I met with Gettysburg they followed a similar model in spirit, organizing programs on the website strictly by alphabet and making use of departments only when administrative scaffolding couldn't be avoided. Eventually we learned the faculty’s reverence for this arrangement was out of deference to one another, since any other organizing principle inflicted a top to bottom ordering of importance, and all programs were, in theory, equally important. (I’m not blowing smoke, either. We proposed departmental organization as an option and several faculty members on one committee were, let’s say, vociferous in their dislike.)

While noble, this presented a couple of unusual challenges. The first was that, being flat—fair is, I think, the better word—the College was ‘showing its underwear,’ exposing its political life on the website and thereby imposing a sort of featurelessness on the user which made certain parts of the site—arguably the most important sections—difficult to use and uninteresting to look at. (That old designerly saying, “if everything is important, then nothing is important,” doesn’t work in the reverse: When nothing is important….)

The bigger trouble, though, is how a design ethic like this can be taken. In the wrong setting deliberate non-design, already a contradiction in terms, is liable to come off less egalitarian and democratic than unimportant and uncared-for.

Recognizing that we saw two ways forward.

Either steer the College toward more traditional ways of web-thinking—which would contemporize the site, achieve basic parity with other schools, but perhaps go against their values—or take a cue from their own attempts, bushwhack our way through a jungle of unknowns, and conceive of a total experience, from brand to content model, based on their liberal arts epistemology.

The four stages of intellectual and ethical development

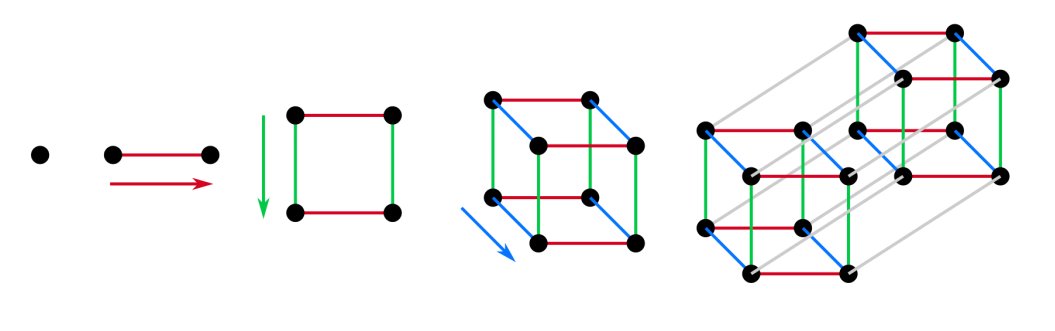

A second and validating source of inspiration came from researcher William G. Perry, whose groundbreaking studies on undergraduates correlated students’ intellectual and ethical development to non-linear positions which he advised educators should look for in their students and tailor their lesson plans to. In short, a student matures from simple dualism (a thing is either this or that, right or wrong), to multiplicity (an individual must make up their own mind), to relativism (one makes peace with uncertainty), and finally commitment (concrete belief—all of these I simplify).

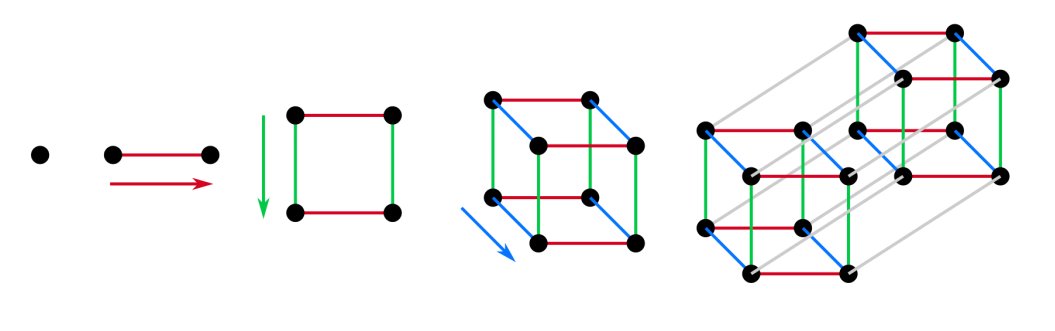

![]()

A way to think about the three main stages: dualism (2d), multiplicity (3d), and relativism (4d). Their presentation implies linear progression, but belief systems can retreat as well as advance. Image source

The difficulty with this scheme is not only that students mature at different speeds and have to be taught accordingly, but that each individual—like the rest of us—contains multitudes: meaning a person who has grown past an either/or view of one topic and found meaning within its many contextual layers likely still has dualistic views on a variety of other subjects. This has obvious implications to coursework and teaching methods but also more broadly can be applied to a person’s value system, in which views such as political positions may not always be in agreement and almost certainly won’t be evenly developed.

I owe a debt to Liz Freedman, an admissions assistant at Butler University, whose brief essay warning against premature major selection brought Perry’s work to my attention. Citing available statistics on major selection and abandonment she makes a strong case for colleges fully prohibiting major selection until at least the sophomore year, the earliest point at which a student's intellectual and ethical development can have matured into “multiplicity”: Perry’s name for the rebellious stage when lived experience has shot through the child’s black and white world and opened the mind to cognitive independence.

As Freedman hints, this is coeval with physical independence: “First-year students are still attempting to understand their own identity and, having lived a majority of their lives under someone else’s guidance, they may not yet be able to come to legitimate conclusions about themselves. This raises the question, without knowing one’s self, how can one effectively choose a major?”

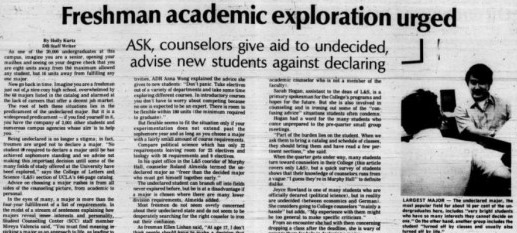

![]()

Scan from a 1974 issue of the Daily Bruin, UCLA’s student paper. Prior to the 1980s it was not uncommon for colleges and universities to dissuade first-years from declaring a major.

So what happens? Well, pressured to declare a major, dualistic students reflexively turn to authority figures for the “right” answer, resulting in an “uneducated, unrelated, and ineffective decision not based on their true personal goals, interests, and values.” (Look at major attrition rates. One of the most flexible and hirable degrees, math, is abandoned by half of all students, either because of missed expectations or poor alignment. That math suffers the highest rate of attrition is probably not a surprise, since mathematics is, by its very nature, perfectly suited to unambiguous dichotomies, and would appeal to worldviews inclined to absolutes.)

Finally, to address the disconnect, Freedman recommends a culture shift toward “the use of appreciative advising, which is asking positive, open-ended questions when helping students consider goals, passions, and interests—all of which are vital aspects of major choice.”

A way to think about the three main stages: dualism (2d), multiplicity (3d), and relativism (4d). Their presentation implies linear progression, but belief systems can retreat as well as advance. Image source

The difficulty with this scheme is not only that students mature at different speeds and have to be taught accordingly, but that each individual—like the rest of us—contains multitudes: meaning a person who has grown past an either/or view of one topic and found meaning within its many contextual layers likely still has dualistic views on a variety of other subjects. This has obvious implications to coursework and teaching methods but also more broadly can be applied to a person’s value system, in which views such as political positions may not always be in agreement and almost certainly won’t be evenly developed.

I owe a debt to Liz Freedman, an admissions assistant at Butler University, whose brief essay warning against premature major selection brought Perry’s work to my attention. Citing available statistics on major selection and abandonment she makes a strong case for colleges fully prohibiting major selection until at least the sophomore year, the earliest point at which a student's intellectual and ethical development can have matured into “multiplicity”: Perry’s name for the rebellious stage when lived experience has shot through the child’s black and white world and opened the mind to cognitive independence.

As Freedman hints, this is coeval with physical independence: “First-year students are still attempting to understand their own identity and, having lived a majority of their lives under someone else’s guidance, they may not yet be able to come to legitimate conclusions about themselves. This raises the question, without knowing one’s self, how can one effectively choose a major?”

So what happens? Well, pressured to declare a major, dualistic students reflexively turn to authority figures for the “right” answer, resulting in an “uneducated, unrelated, and ineffective decision not based on their true personal goals, interests, and values.” (Look at major attrition rates. One of the most flexible and hirable degrees, math, is abandoned by half of all students, either because of missed expectations or poor alignment. That math suffers the highest rate of attrition is probably not a surprise, since mathematics is, by its very nature, perfectly suited to unambiguous dichotomies, and would appeal to worldviews inclined to absolutes.)

Finally, to address the disconnect, Freedman recommends a culture shift toward “the use of appreciative advising, which is asking positive, open-ended questions when helping students consider goals, passions, and interests—all of which are vital aspects of major choice.”

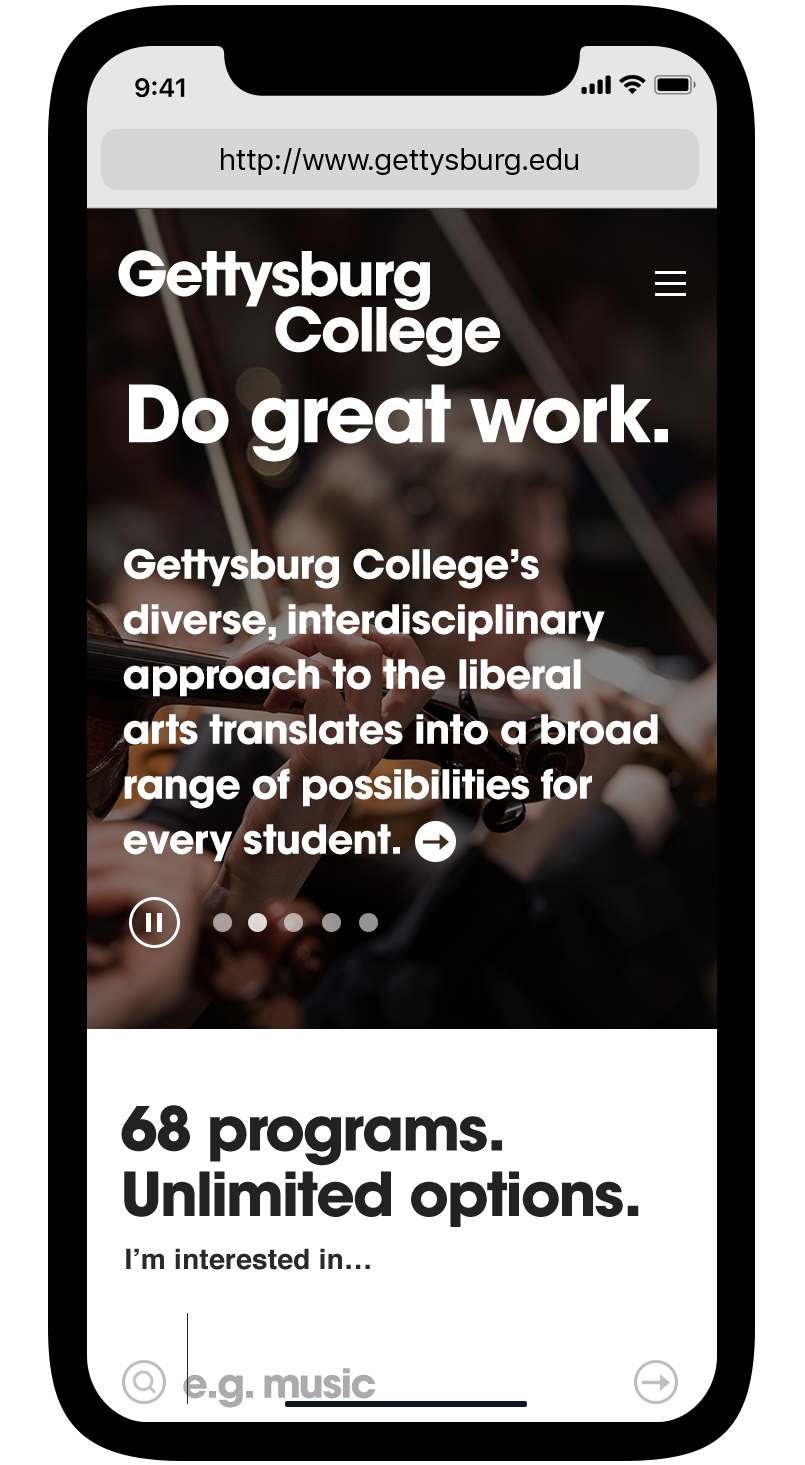

Open-ended search / confessional

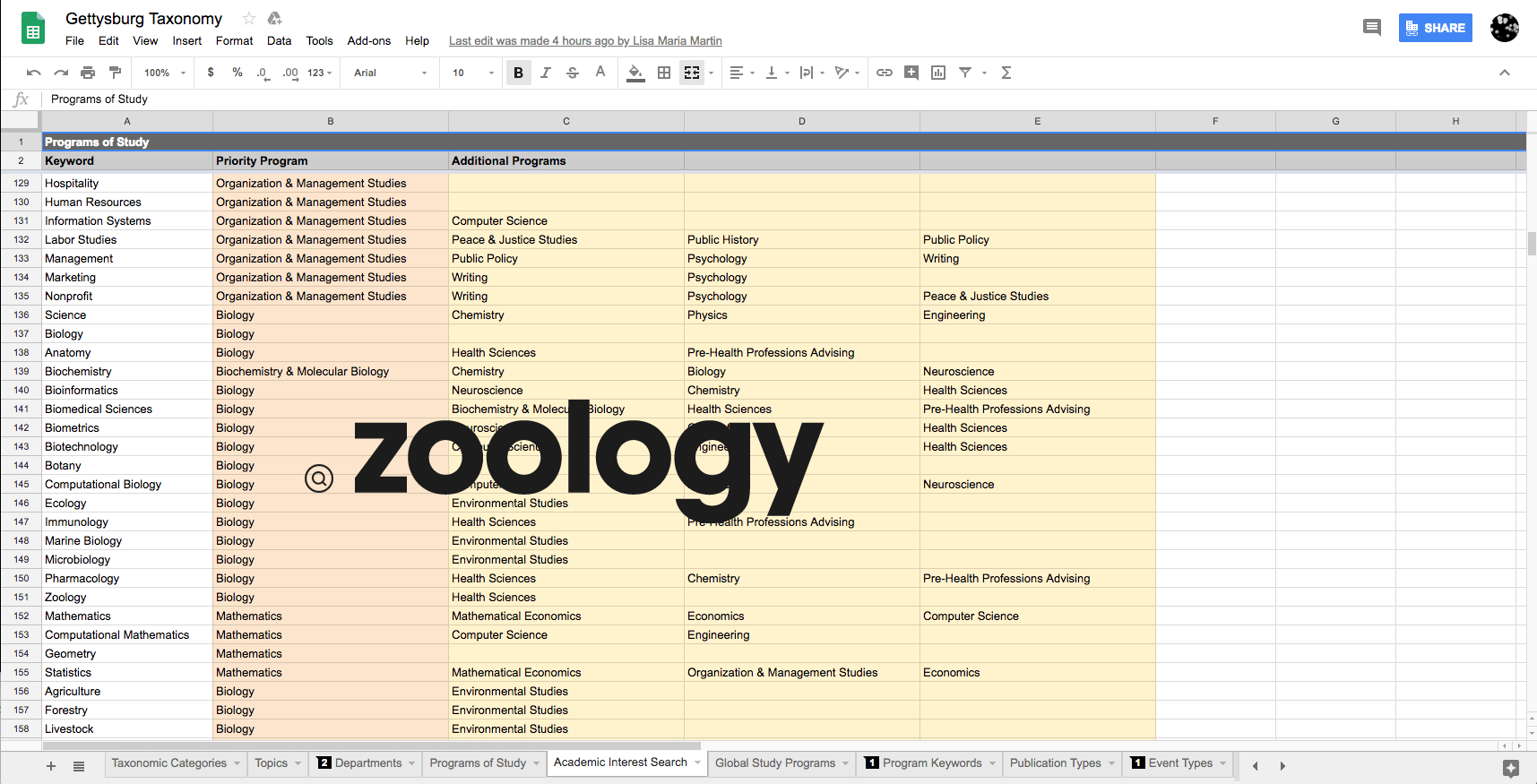

Illustration of how majors, partner programs, courses, and student stories are layered into searches for interest keywords based on taxonomic relationships and relevancy.

Supporting research

Several other sources, including a study of how these decisions may affect students into adulthood, helped guide the UX strategy and ultimately sell the concept through committee.

The tl;dr of all that research is, the decline in support for the humanities, and the rush to pick a major tied to a high financial payout—nearly all of which are in STEM, save maybe law—can be connected to economic policies and attitudes rooted in Reagan-era legislation.

As a consequence Millennials don’t find the same meaning in work as previous generations have because the limitless future promised by neoliberalism demanded they be inculcated into generalist automata for the sake of hitherto unknown methods of globalized production. They have jobs—many jobs, sometimes several at one time, in fact—but not careers, and few identify with any particular calling, all of which rolls into the drastic decline in work identity. And perhaps this would be fine, if it meant that the Protestant work ethic had loosened its grip on labor as a means of stratifying American society. Of course, we know this isn’t true. Remote communication tools have all but eliminated the shrinking hyphen in the home-office divide such that Americans can now claim the dubious distinction of “most overworked in the world.” So if Perry is right about meaning being essential to identity, and we spend most of our waking life working, then we’ve basically denied an entire generation an essential metaphysics—and not only by pushing them away from the humanities.

On the quantitative end of things, neuroscientists recently observed that the brain doesn’t actually develop by age 10, as long believed, but much later, sometime in the mid-20s, with the frontal lobes, the locus of decision making, the last to fully connect. The study which NPR reported on in 2010 concludes—to no one’s surprise—that teenagers lack foresight at a very basic, physiological level, a fact which only time and lived experience can correct.

Which leads me to think either Perry was ahead of his time or, more likely, we have fallen behind in ours. Marilynne Robinson: “It has been characteristic of American education that it has offered students a great variety of fields of study and a great freedom to choose among them. It has served as a mighty paradigm for the kind of self-discovery Americans have historically valued. Now this idea has gone into eclipse.”

The tl;dr of all that research is, the decline in support for the humanities, and the rush to pick a major tied to a high financial payout—nearly all of which are in STEM, save maybe law—can be connected to economic policies and attitudes rooted in Reagan-era legislation.

As a consequence Millennials don’t find the same meaning in work as previous generations have because the limitless future promised by neoliberalism demanded they be inculcated into generalist automata for the sake of hitherto unknown methods of globalized production. They have jobs—many jobs, sometimes several at one time, in fact—but not careers, and few identify with any particular calling, all of which rolls into the drastic decline in work identity. And perhaps this would be fine, if it meant that the Protestant work ethic had loosened its grip on labor as a means of stratifying American society. Of course, we know this isn’t true. Remote communication tools have all but eliminated the shrinking hyphen in the home-office divide such that Americans can now claim the dubious distinction of “most overworked in the world.” So if Perry is right about meaning being essential to identity, and we spend most of our waking life working, then we’ve basically denied an entire generation an essential metaphysics—and not only by pushing them away from the humanities.

On the quantitative end of things, neuroscientists recently observed that the brain doesn’t actually develop by age 10, as long believed, but much later, sometime in the mid-20s, with the frontal lobes, the locus of decision making, the last to fully connect. The study which NPR reported on in 2010 concludes—to no one’s surprise—that teenagers lack foresight at a very basic, physiological level, a fact which only time and lived experience can correct.

Which leads me to think either Perry was ahead of his time or, more likely, we have fallen behind in ours. Marilynne Robinson: “It has been characteristic of American education that it has offered students a great variety of fields of study and a great freedom to choose among them. It has served as a mighty paradigm for the kind of self-discovery Americans have historically valued. Now this idea has gone into eclipse.”

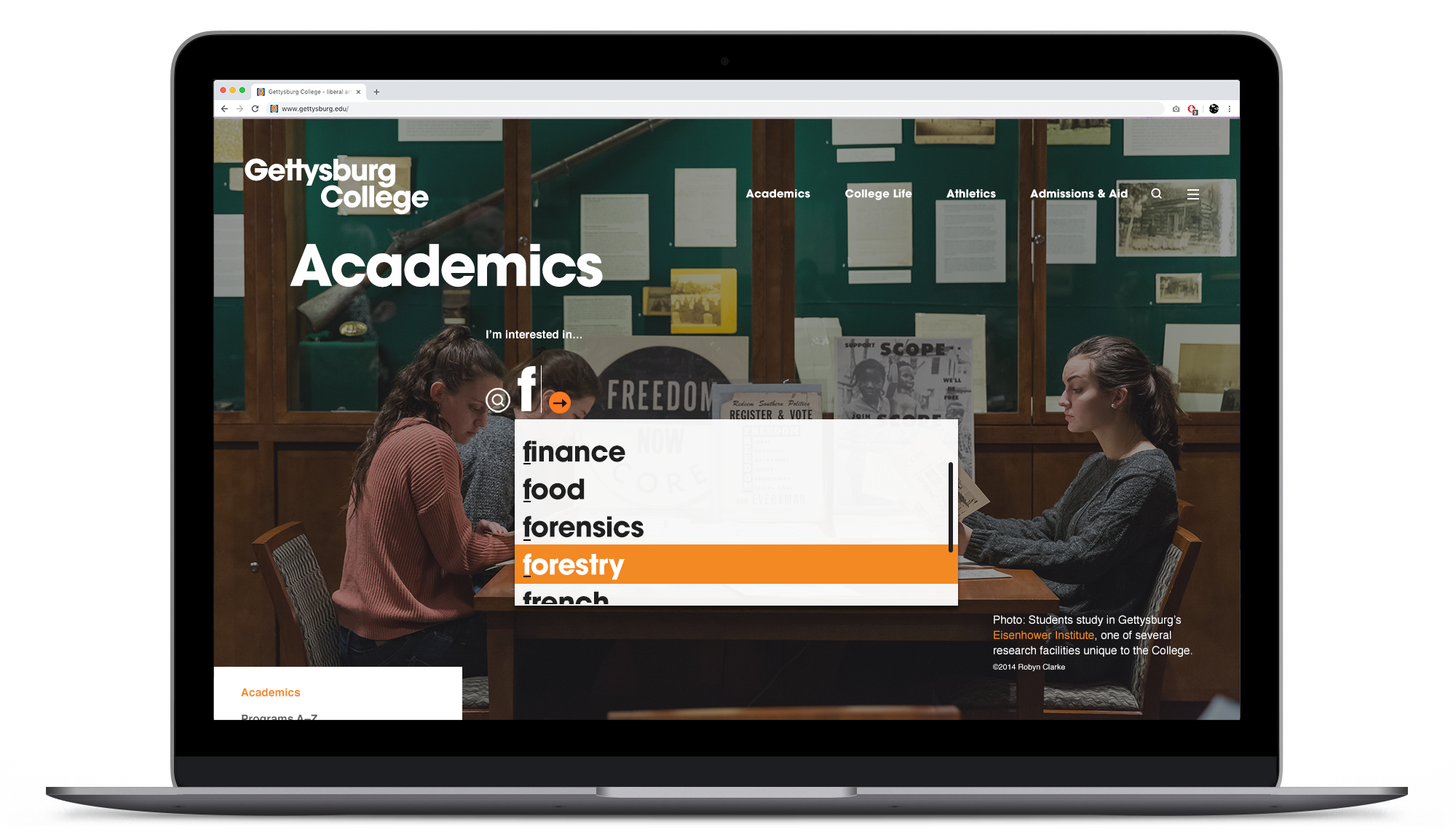

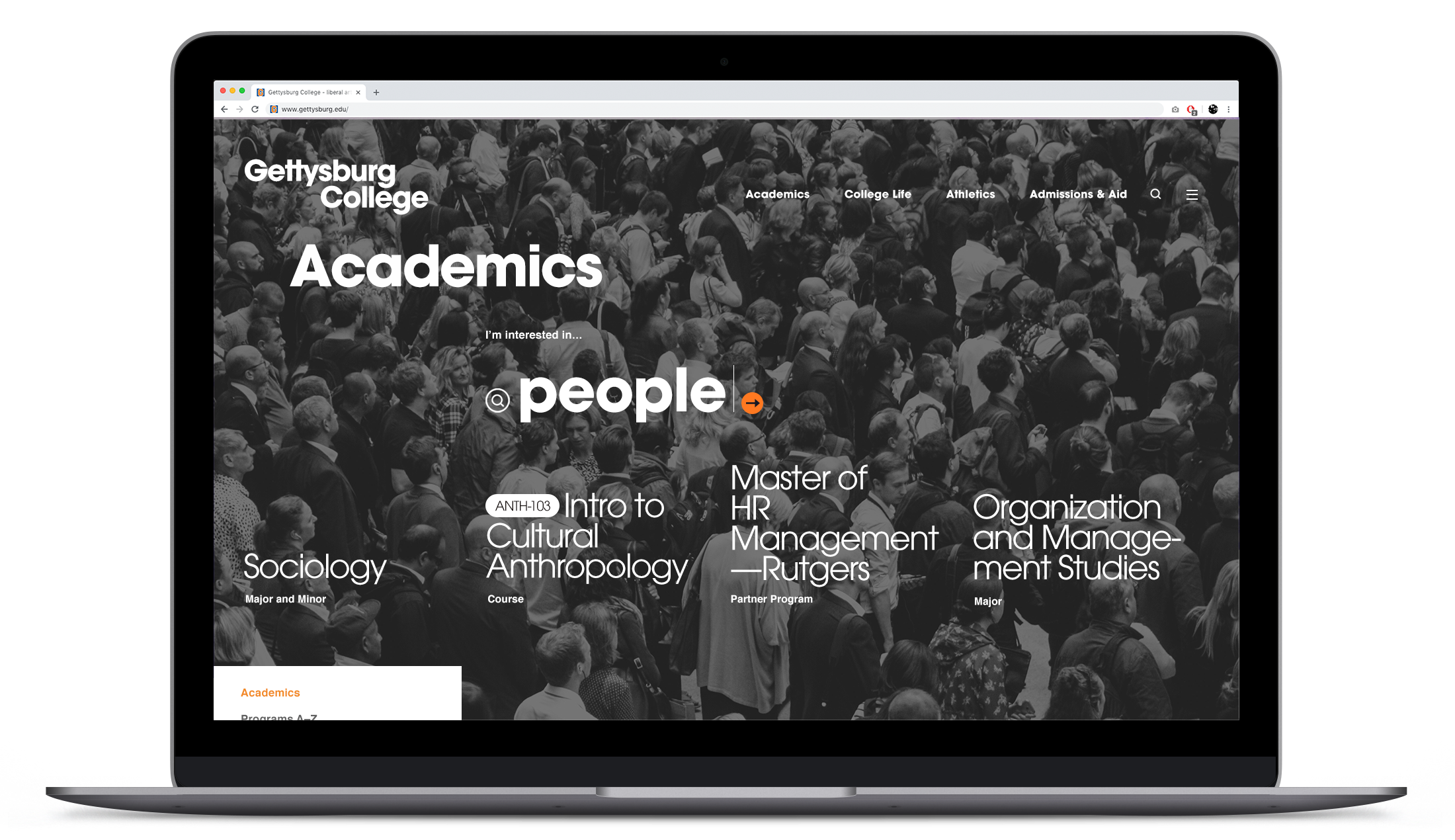

The search was pre-populated with terms which mapped both directly and indirectly to major programs.

Broad, abstract keywords yielded some of the more interesting branching paths.

The aim was to give confidence that, at Gettysburg, students could figure it out—whatever it ends up being.

Broad, abstract keywords yielded some of the more interesting branching paths.

The aim was to give confidence that, at Gettysburg, students could figure it out—whatever it ends up being.

’70s throwback: “This is exactly what the liberal arts is supposed to do”

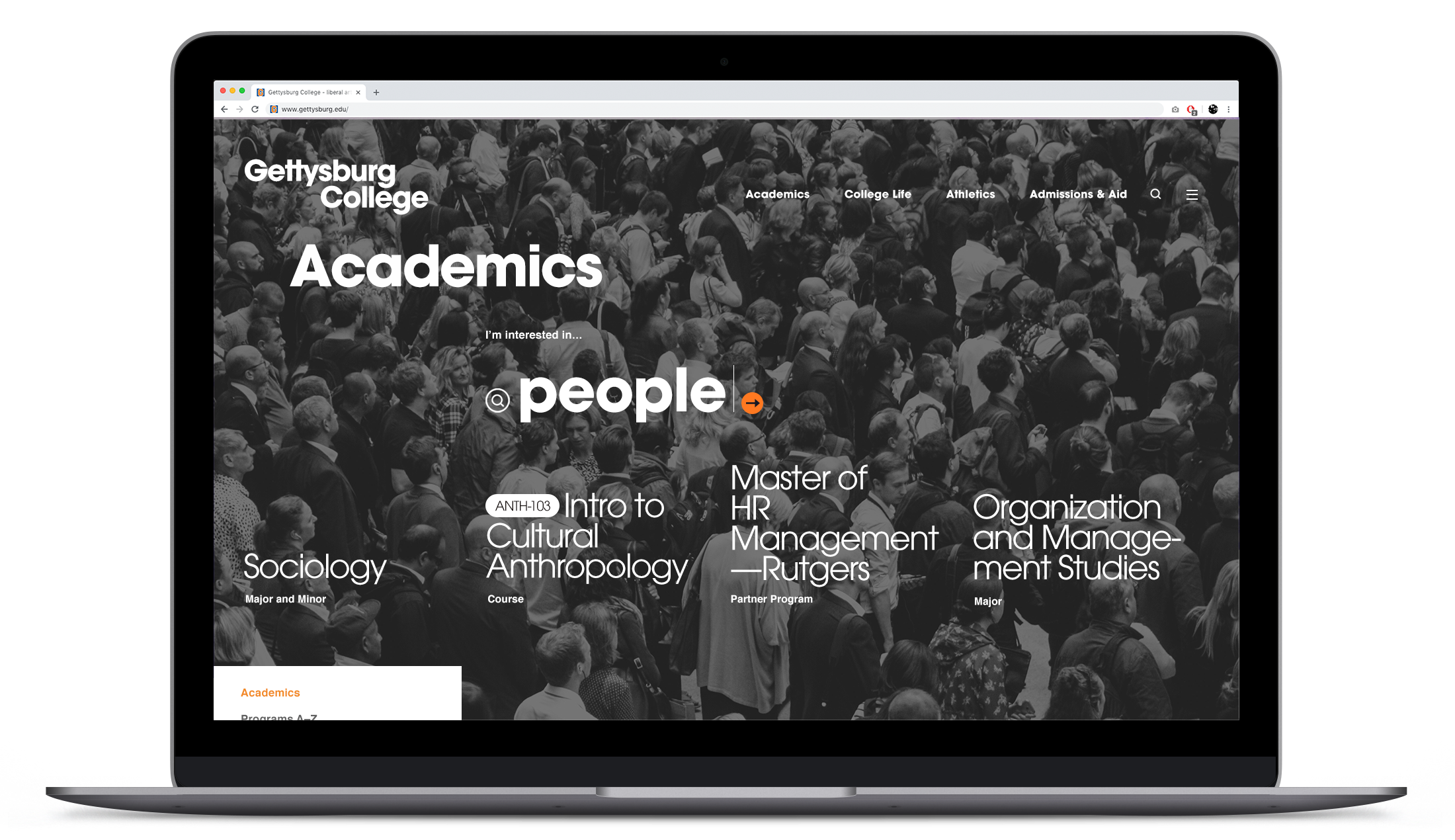

Inspired by Freedman’s suggestion for open-ended, exploratory dialogue, the academic interest search collates and contextualizes the various academic enrichment opportunities tied to a keyword. These are not programmatically driven (see IFAW) but tightly woven together by subject matter experts who have the career insights to do professional advising. The point is to provide, in measured doses, wide exposure to unexpected disciplines or activities which connect, sometimes unexpectedly, to the student's interest or preferences.

For example, a young person vaguely interested in “data” may have been prejudiced to mathematics, statistics, economics. This is the direction a generalized audience would point her. But manipulating data structures is essential to a host of other disciplines not typically associated with numerical patterns: wildlife biology, climate science, anthropology, forestry. In fact I read something earlier this year by a data scientist theologian, a paradox if there ever was one: binary absolutes in league with the ineffable. No doubt there are even stranger hybrids. And therein lies the beauty of a science-sensitive liberal arts education: how the vital commingling of heterogenous knowledge systems engenders newness, innovation, and most importantly, self-discovery. Multiplicity rests on this.

The question, of course, is whether a college website can bump a student from one mental position to another. No, I don't think it can. But I do believe good design and good framing can help prime students to see their options for what they truly are in a liberal arts tradition: like themselves, deeply interconnected, unfinished, and still unfolding. And as one excited faculty member said after a presentation: “This is exactly what the liberal arts is supposed to do.”

For example, a young person vaguely interested in “data” may have been prejudiced to mathematics, statistics, economics. This is the direction a generalized audience would point her. But manipulating data structures is essential to a host of other disciplines not typically associated with numerical patterns: wildlife biology, climate science, anthropology, forestry. In fact I read something earlier this year by a data scientist theologian, a paradox if there ever was one: binary absolutes in league with the ineffable. No doubt there are even stranger hybrids. And therein lies the beauty of a science-sensitive liberal arts education: how the vital commingling of heterogenous knowledge systems engenders newness, innovation, and most importantly, self-discovery. Multiplicity rests on this.

The question, of course, is whether a college website can bump a student from one mental position to another. No, I don't think it can. But I do believe good design and good framing can help prime students to see their options for what they truly are in a liberal arts tradition: like themselves, deeply interconnected, unfinished, and still unfolding. And as one excited faculty member said after a presentation: “This is exactly what the liberal arts is supposed to do.”