International Fund for Animal Welfare: content strategy and architecture proof-of-concept for advocacy, education, and conversion

Research, direction, mockups, datavis. Made at Happy Cog, November 2016.

The International Fund for Animal Welfare’s (IFAW) belief in the intrinsic value of all animal life is demonstrated in the rescue, rehabilitation, and rewilding of distressed members of both protected and unprotected species. Such stories help architect their fundraising and outreach strategy.

This is in contrast to top-down organizations such as the World Wildlife Foundation, who don’t allocate funds toward rescue and rehab if the affect on the species population doesn’t warrant it; that, to them, is money better spent elsewhere.

While the aims of both are arguably the same, in terms of the general public IFAW’s value system often works against the organization’s broader goals. This can largely be attributed to the rescue and rehab of abused, domesticated house and farm animals. Most of their repeat and estate donors fall into this camp of “dog and cat lovers.”

But IFAW is a bona fide conservation organization on par with the WWF, responsible for, among other programs, starting and managing a massive counter-poaching initiative in Kenya under the leadership of a former counter-terrorist Air Force officer turned animal advocate.

Rightly situating them in that context was the primary goal of a new digital strategy.

This is in contrast to top-down organizations such as the World Wildlife Foundation, who don’t allocate funds toward rescue and rehab if the affect on the species population doesn’t warrant it; that, to them, is money better spent elsewhere.

While the aims of both are arguably the same, in terms of the general public IFAW’s value system often works against the organization’s broader goals. This can largely be attributed to the rescue and rehab of abused, domesticated house and farm animals. Most of their repeat and estate donors fall into this camp of “dog and cat lovers.”

But IFAW is a bona fide conservation organization on par with the WWF, responsible for, among other programs, starting and managing a massive counter-poaching initiative in Kenya under the leadership of a former counter-terrorist Air Force officer turned animal advocate.

Rightly situating them in that context was the primary goal of a new digital strategy.

Their mission isn’t inherently incompatible with the goal of rebranding as a conservation charity.

Two problems undermined their digital strategy.

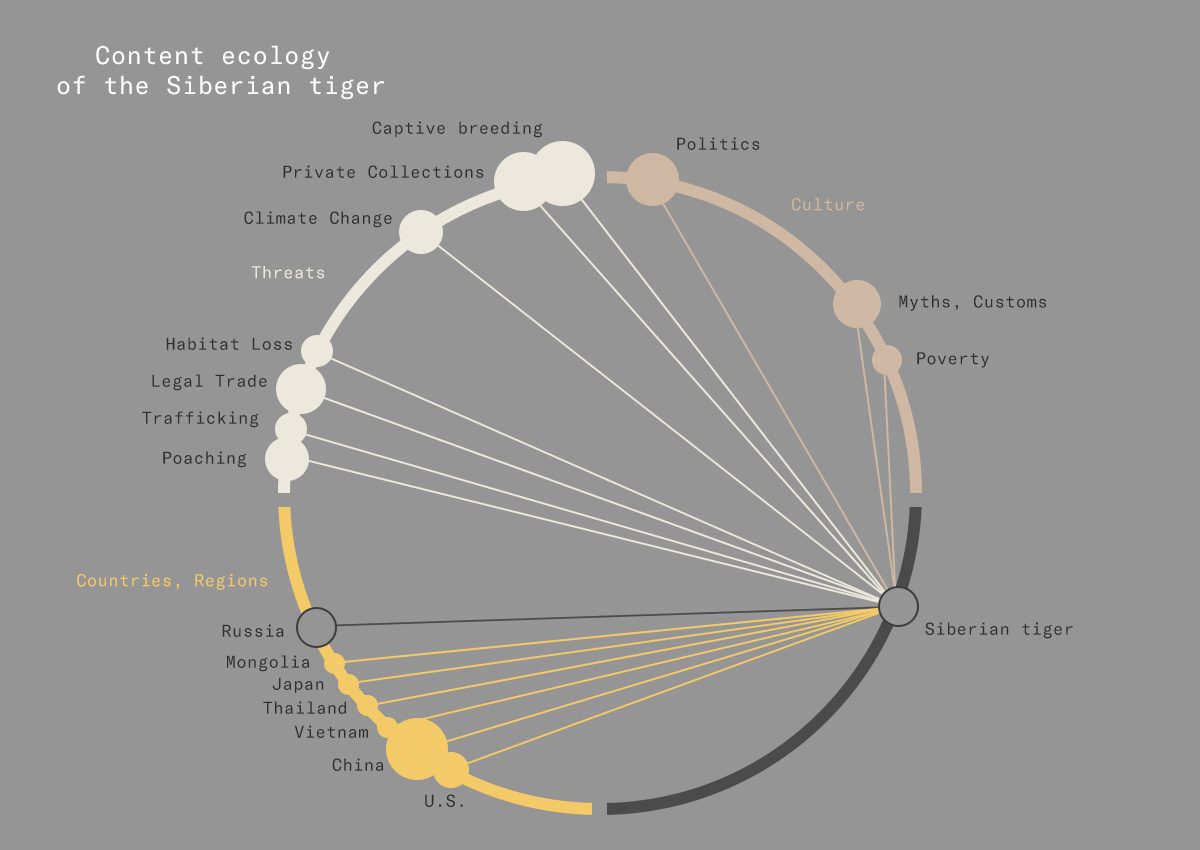

One, the site was compartmentalized according to programs, and those sections cross-pollinated either not at all or by visual likeness (cetaceans, big cats, thick-hided megafauna), inhibiting circulation between sections.

Two, no connection was made to the exigencies of human beings and their affect on animalkind.

That said the wrenching stories are still key. I read six activists’ memoirs and invariably each author reports a moment when they locked eyes with a distressed animal, and each interprets this passing instant as a nonverbal entreaty of help. IFAW’s stories tug on the same strings.

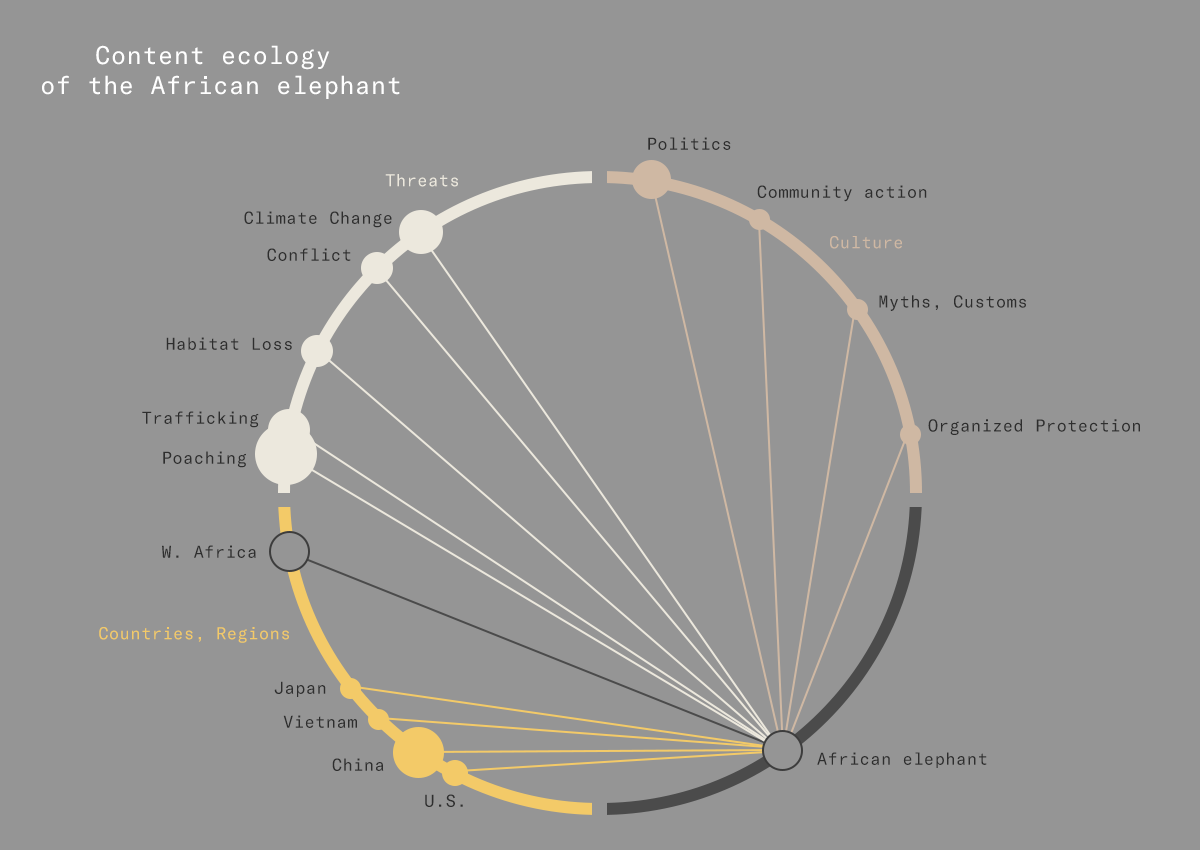

But in five of the six cases this initial interaction—what I referred to as a “gateway animal”—blossomed into dedication for another species: their “passion animal.” These two species were not connected by taxonomic order or visual likeness but by the shared abuses and indifferent pressures placed on them by human civilization.

This confirms something anthropologists know very well: we humans think in terms of stories, not in categories.

Two problems undermined their digital strategy.

One, the site was compartmentalized according to programs, and those sections cross-pollinated either not at all or by visual likeness (cetaceans, big cats, thick-hided megafauna), inhibiting circulation between sections.

Two, no connection was made to the exigencies of human beings and their affect on animalkind.

That said the wrenching stories are still key. I read six activists’ memoirs and invariably each author reports a moment when they locked eyes with a distressed animal, and each interprets this passing instant as a nonverbal entreaty of help. IFAW’s stories tug on the same strings.

But in five of the six cases this initial interaction—what I referred to as a “gateway animal”—blossomed into dedication for another species: their “passion animal.” These two species were not connected by taxonomic order or visual likeness but by the shared abuses and indifferent pressures placed on them by human civilization.

This confirms something anthropologists know very well: we humans think in terms of stories, not in categories.

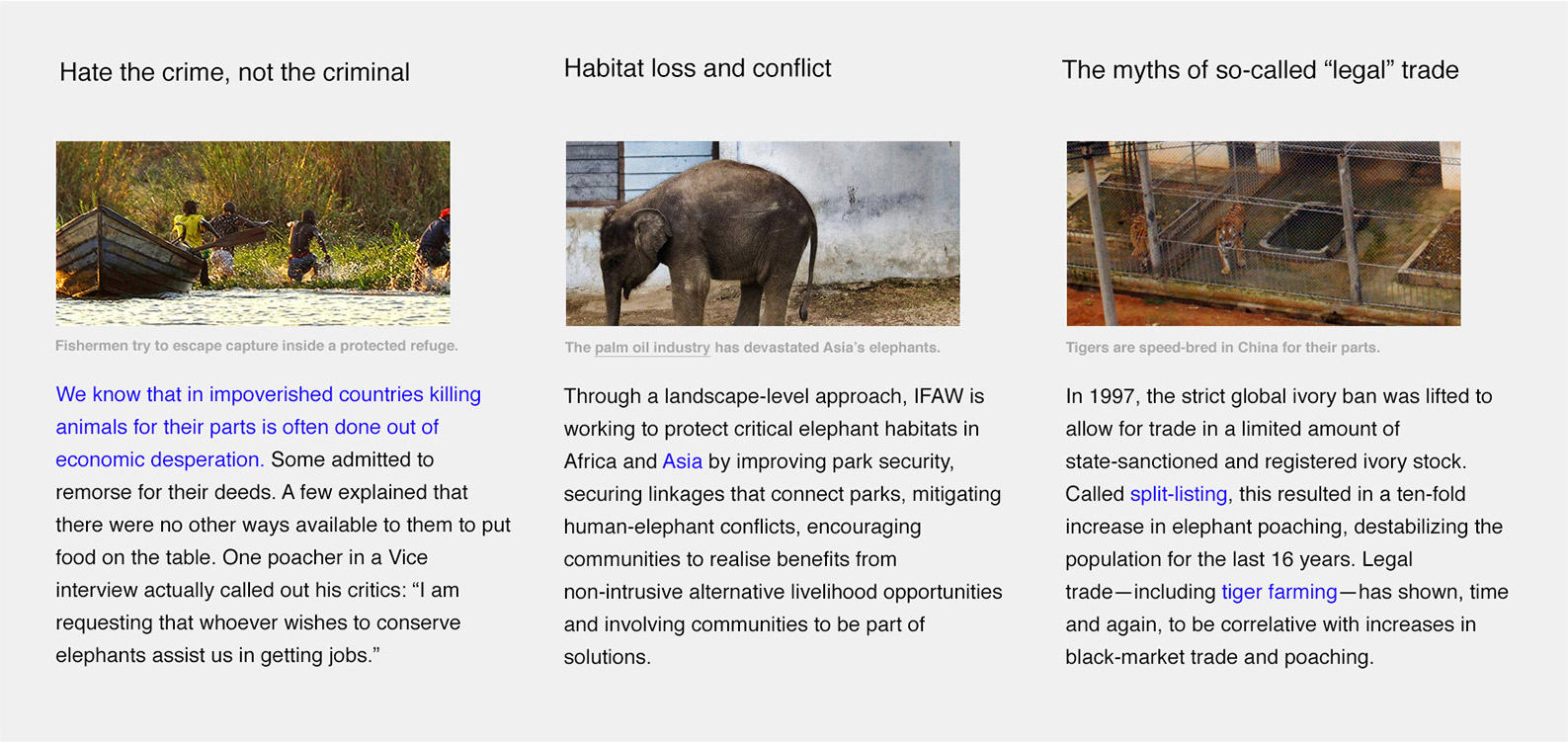

Humans at the center

We’re a complicated problem to unravel. It’s easy to make bogeymen of people like poachers. It’s much less easy to put them in the appropriate context.

Understanding that inequality, globalization, and colonialism are the actual root causes responsible for human-wildlife conflict can dramatically increase gains in conservation by placing humankind into a greater global ecology, rather than the usual pernicious and incorrect human vs. nature dichotomy.

“For every two tusks a whole village has been destroyed, every twenty tusks have been obtained at the price of a district with all its people, villages, and plantations. It is simply incredible that, because ivory is required for ornaments or billiard games, the rich heart of Africa should be laid waste ... that populations, tribes, and nations should be utterly destroyed.”—Peter Matthiessen, African Silences (1991)

In the end this arbitrary duality only pits us against ourselves. Until we perceive the natural world less as a zoo, a kind of observatory we exist apart from, than an interconnected web of which we’re highly dependent, there can’t be meaningful change. (Even my own repeated use of “animalkind” and “humankind” evinces a deep-seated prejudice.)

The principal enemy is then not the poacher, or the smuggler, or even the buyer, but the entire human part of the chain. We are each complicit by degrees.

The problem is, we aren’t informed.

“Informed sympathy is empathy, expressed as compassionate understanding. Rational empathy is the only basis for ethically responsible behavior.” —M.W. Fox, “Empathy, Humaneness and Animal Welfare” (1984)

Understanding that inequality, globalization, and colonialism are the actual root causes responsible for human-wildlife conflict can dramatically increase gains in conservation by placing humankind into a greater global ecology, rather than the usual pernicious and incorrect human vs. nature dichotomy.

“For every two tusks a whole village has been destroyed, every twenty tusks have been obtained at the price of a district with all its people, villages, and plantations. It is simply incredible that, because ivory is required for ornaments or billiard games, the rich heart of Africa should be laid waste ... that populations, tribes, and nations should be utterly destroyed.”—Peter Matthiessen, African Silences (1991)

In the end this arbitrary duality only pits us against ourselves. Until we perceive the natural world less as a zoo, a kind of observatory we exist apart from, than an interconnected web of which we’re highly dependent, there can’t be meaningful change. (Even my own repeated use of “animalkind” and “humankind” evinces a deep-seated prejudice.)

The principal enemy is then not the poacher, or the smuggler, or even the buyer, but the entire human part of the chain. We are each complicit by degrees.

The problem is, we aren’t informed.

“Informed sympathy is empathy, expressed as compassionate understanding. Rational empathy is the only basis for ethically responsible behavior.” —M.W. Fox, “Empathy, Humaneness and Animal Welfare” (1984)

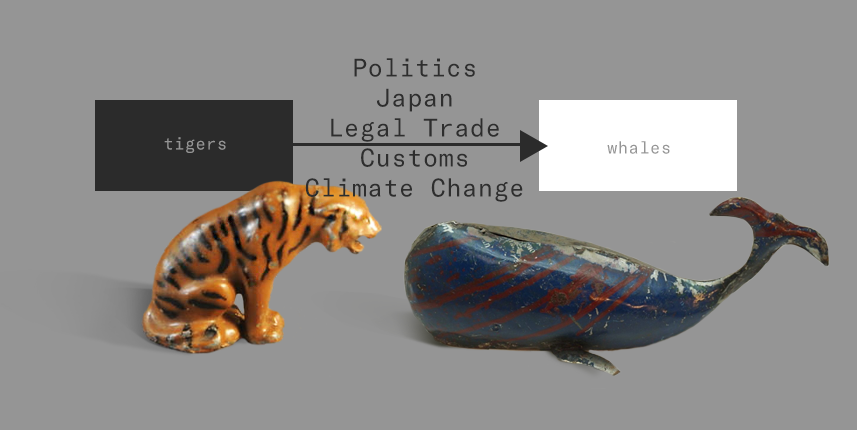

Topic center proofs-of-concept: Programmatically generating connections according to human pressures

The new experience was engineered around “topic centers,” single pages assembled by modular content blocks. These pages would be lightly curated—headlines, photos—but otherwise be programmatically generated by the content model, which would be recalibrated every so often based on analytic reviews. This permitted the creation of additional topic centers as new threats arose or became better understood. In these wireframes the site navigation has been stripped to focus on the chance possibilities inherent to content as a wayfinding mechanism.

Breakdown

Header image and messaging

Past a certain threshold all numbers feel the same. Most people can’t comprehend a difference between 100,000 and 1,000,000 because these are not numbers we encounter routinely, even in an urban setting. I know some twenty million people will pass through New York today, but in my mind one numberless mob blends into another. Every statistic of this magnitude needs help being visualized.

Past a certain threshold all numbers feel the same. Most people can’t comprehend a difference between 100,000 and 1,000,000 because these are not numbers we encounter routinely, even in an urban setting. I know some twenty million people will pass through New York today, but in my mind one numberless mob blends into another. Every statistic of this magnitude needs help being visualized.

Issue overview and history

The hero image provides scene setting. The content immediately below acts like a recap. Note how much of the summary is bent toward human stories.

The point of all marketing material is to simultaneously raise awareness and raise funds. Content priority should be judged along these axes. Does it inform? Does it explain how money will be used?

These answers don’t have to be didactic or overly explicit. Vietnam committing to destroying confiscated ivory and rhino horn—taking it out of circulation—suggests progress, hope. People need to know they’re not contributing to a lost cause. Conservation is an endlessly optimistic pursuit.

The hero image provides scene setting. The content immediately below acts like a recap. Note how much of the summary is bent toward human stories.

The point of all marketing material is to simultaneously raise awareness and raise funds. Content priority should be judged along these axes. Does it inform? Does it explain how money will be used?

These answers don’t have to be didactic or overly explicit. Vietnam committing to destroying confiscated ivory and rhino horn—taking it out of circulation—suggests progress, hope. People need to know they’re not contributing to a lost cause. Conservation is an endlessly optimistic pursuit.

Deep dive education

In the narrative flow this would be close to the middle of the journalism pyramid. Only a thin band (as conceived in this wireframe), but the meat of the experience. While the web is a medium well suited to facilitating serendipitous discovery, you can’t manufacture it. Thus the point here isn’t to create a banal “you might also like” recommendation module but instead open up a series of possible related pathways into animals and issues connected by narrative rather than facile visual similarity.

In the narrative flow this would be close to the middle of the journalism pyramid. Only a thin band (as conceived in this wireframe), but the meat of the experience. While the web is a medium well suited to facilitating serendipitous discovery, you can’t manufacture it. Thus the point here isn’t to create a banal “you might also like” recommendation module but instead open up a series of possible related pathways into animals and issues connected by narrative rather than facile visual similarity.

Evidence

The first thing that should be said is people like video a lot less than certain experts say. (Note that most of those experts are in media buying and want to sell you pre-roll.) Even great video content is a bad lead. People want to know it’ll be worth their time first. In the IFAW topic center templates I proposed it come near the bottom—the showiest piece of evidence placed near the donate button.

The first thing that should be said is people like video a lot less than certain experts say. (Note that most of those experts are in media buying and want to sell you pre-roll.) Even great video content is a bad lead. People want to know it’ll be worth their time first. In the IFAW topic center templates I proposed it come near the bottom—the showiest piece of evidence placed near the donate button.

Then finally: Make it local, make it actionable

In the developed world some of these issues aren’t seen as domestic problems, meanwhile the U.S. is among the largest markets for various animals and their parts. There are more tigers in captivity in the U.S. than exist in the wild.

In any event, though it’s less common that a person will donate on a first visit (unless moved by some crisis) it’s enough for the moment to provide them with information and contagious anecdotes (“you know I heard…”) at every opportunity.

In the developed world some of these issues aren’t seen as domestic problems, meanwhile the U.S. is among the largest markets for various animals and their parts. There are more tigers in captivity in the U.S. than exist in the wild.

In any event, though it’s less common that a person will donate on a first visit (unless moved by some crisis) it’s enough for the moment to provide them with information and contagious anecdotes (“you know I heard…”) at every opportunity.

Continued engagement

Though the sign-up allows for animal-centric options, new discoveries can be made obliquely through email alerts. For instance, “legal” trade of animal parts is often used as a cover to effectively launder and subsidize black market trade. This connects tigers to, among others, rhinos, elephants, even whales (the Japanese still allow minke hunts for “scientific research,” the whale meat ending up on restaurant menus). In the end the hope is that cold leads or one-time donors will become repeat if not regular donors through a steady stream of varied communications.