Rogers on Demand: Exploring a futurescape

Digital product design. Art direction, design.

Made at Empathy Lab, 2011.

Made at Empathy Lab, 2011.

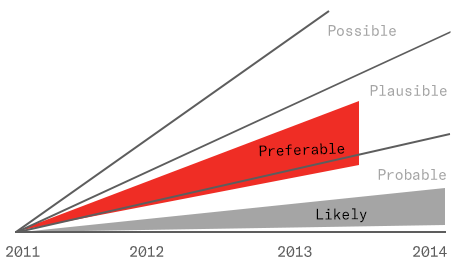

In the book Speculative Everything, authors Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby describe a three-cone model for speculative design thinking:

The first cone, the probable, “is where most designers operate.” It’s what we can assume will occur with a reasonable amount of certainty.

Next there’s the plausible, for “exploring alternative futures” which can help ready an organization for “a number of different futures.” Plausible futures have a direct link to the present and are not technological fantasy.

And last, the possible, “the space of speculative culture —writing, cinema, science fiction—” where we conceive of loosely believable events serving to “make [the impossible] acceptable.”

To these three Dunne and Raby introduce a fourth cone, a shaded area of preferable futures: imagined realities which engender discussion and debate “about the futures people really want.” By speculating smartly, the designer “can help set in place today factors that will increase the probability of more desirable futures happening.”

![]()

We can apply the cone model to any kind of design—all design is to some degree speculative—but in my own experience I find it describes most closely the creative roadmapping involved in product design.

The first cone, the probable, “is where most designers operate.” It’s what we can assume will occur with a reasonable amount of certainty.

Next there’s the plausible, for “exploring alternative futures” which can help ready an organization for “a number of different futures.” Plausible futures have a direct link to the present and are not technological fantasy.

And last, the possible, “the space of speculative culture —writing, cinema, science fiction—” where we conceive of loosely believable events serving to “make [the impossible] acceptable.”

To these three Dunne and Raby introduce a fourth cone, a shaded area of preferable futures: imagined realities which engender discussion and debate “about the futures people really want.” By speculating smartly, the designer “can help set in place today factors that will increase the probability of more desirable futures happening.”

We can apply the cone model to any kind of design—all design is to some degree speculative—but in my own experience I find it describes most closely the creative roadmapping involved in product design.

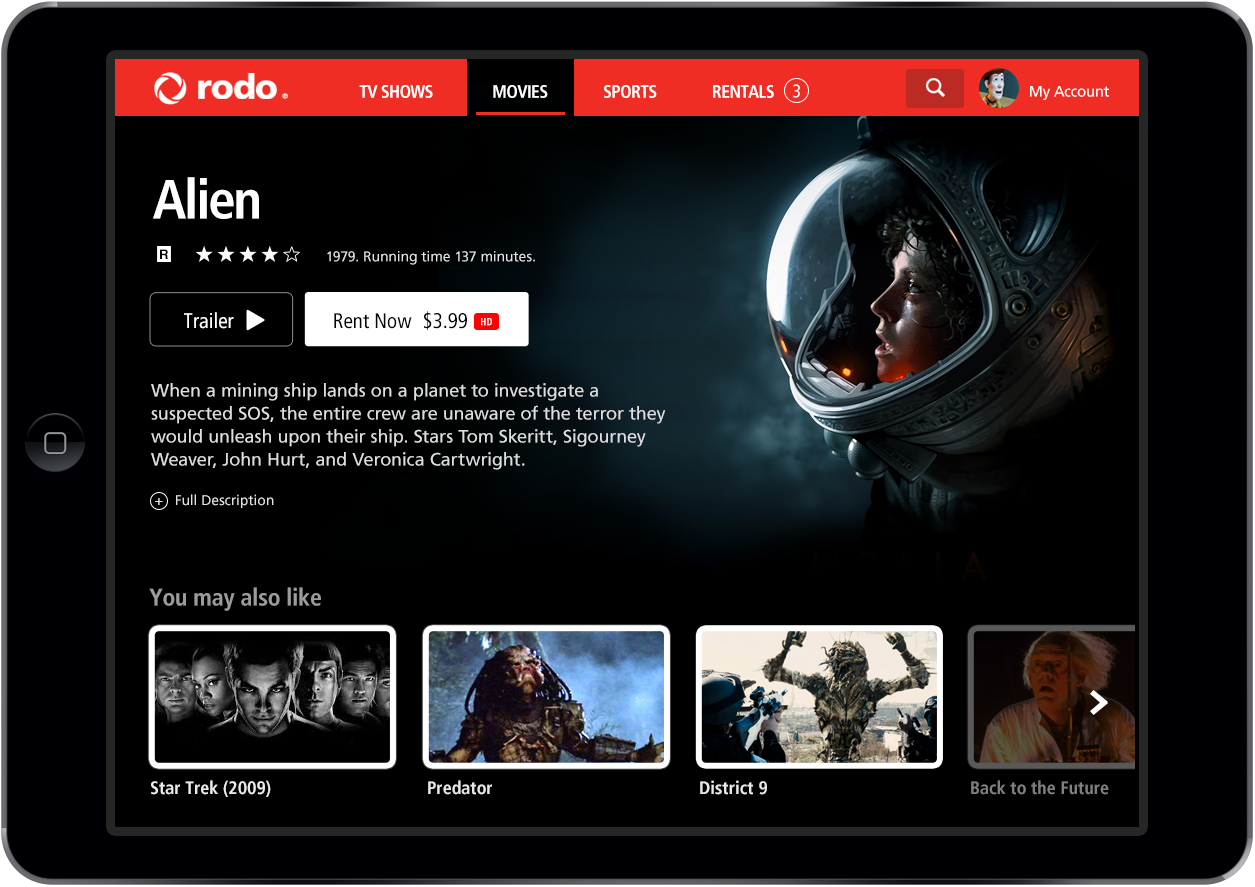

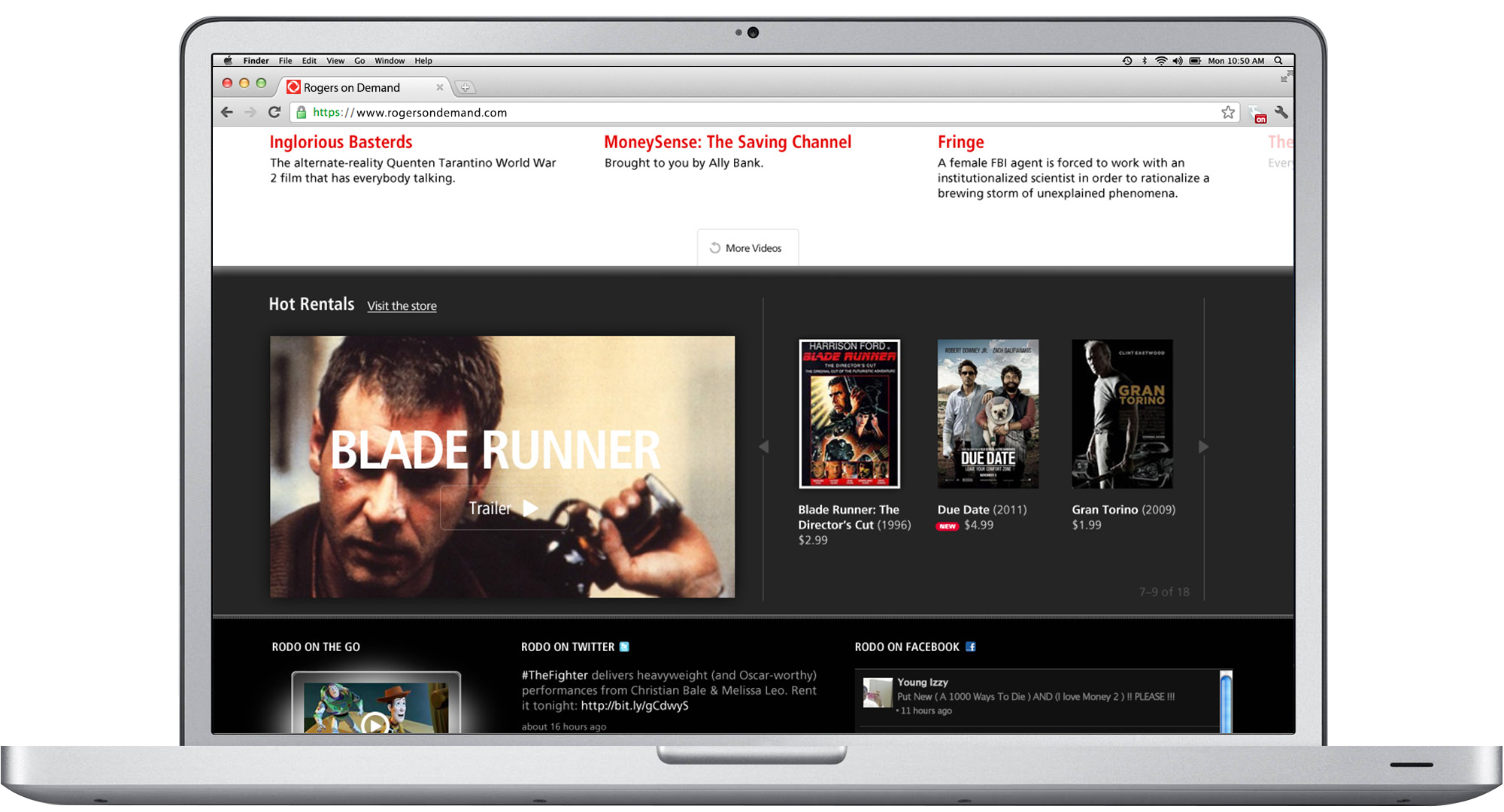

Rogers on Demand Online began as a speculative comp I designed for a pitch in 2008. The year before Netflix had just expanded into streaming media. It was enough to win the gig, and a subsequent iteration imagined the service as its own sub-brand of Rogers, uniquely named and nuanced, for which Rogers had contracted a branding partner. This version soft-launched in 2009. Following two years of Agile sprints the service expanded into the experience early speculation promised.

But two years on the service was at the mercy of decisions made without the benefit of hindsight: much of the site had been parceled and sold to channel partners who were obfuscating the RODO brand with their own, neither the architecture nor interface aged well—the set-top box translated poorly to the we—and the performance was sagging under the weight of an ad model ill-suited to a video platform. The service needed retooling from the ground up.

The speculative comps shown here—a homepage and iPad and iPhone apps—were some of the result of that speculative exercise.

“This potential to use the language of design to pose questions, provoke and inspire is conceptual design’s defining feature,” wrote Dunne and Raby.

Which isn’t an indictment of incrementalism. Product design this size doesn’t generally work on a major-release model. But by its nature incrementalism allows for only a narrow, predictable future that limits the freedom of the imagination to wander into newness and “unsettle the present.”

Futurescaping, though, is an explosion, a rewriting of the beginning, a chance to act on if-I-knew-then-what-I-know-now, the chrysalis by which we might actually make the idealized and unreal, real.

But two years on the service was at the mercy of decisions made without the benefit of hindsight: much of the site had been parceled and sold to channel partners who were obfuscating the RODO brand with their own, neither the architecture nor interface aged well—the set-top box translated poorly to the we—and the performance was sagging under the weight of an ad model ill-suited to a video platform. The service needed retooling from the ground up.

The speculative comps shown here—a homepage and iPad and iPhone apps—were some of the result of that speculative exercise.

“This potential to use the language of design to pose questions, provoke and inspire is conceptual design’s defining feature,” wrote Dunne and Raby.

Which isn’t an indictment of incrementalism. Product design this size doesn’t generally work on a major-release model. But by its nature incrementalism allows for only a narrow, predictable future that limits the freedom of the imagination to wander into newness and “unsettle the present.”

Futurescaping, though, is an explosion, a rewriting of the beginning, a chance to act on if-I-knew-then-what-I-know-now, the chrysalis by which we might actually make the idealized and unreal, real.