White House

Correspondents’ Association (WHCA)

rebrand: Research, notes, and designs for integrative counter-propaganda.

Digital + print. Strategy, concept, design, copy. Preferred execution, not selected. Made at Happy Cog, late 2017 through early 2018.

Above: White House correspondent April Ryan’s hand. © 2017 AP/Alex Brandon (for POC only).

Different strokes

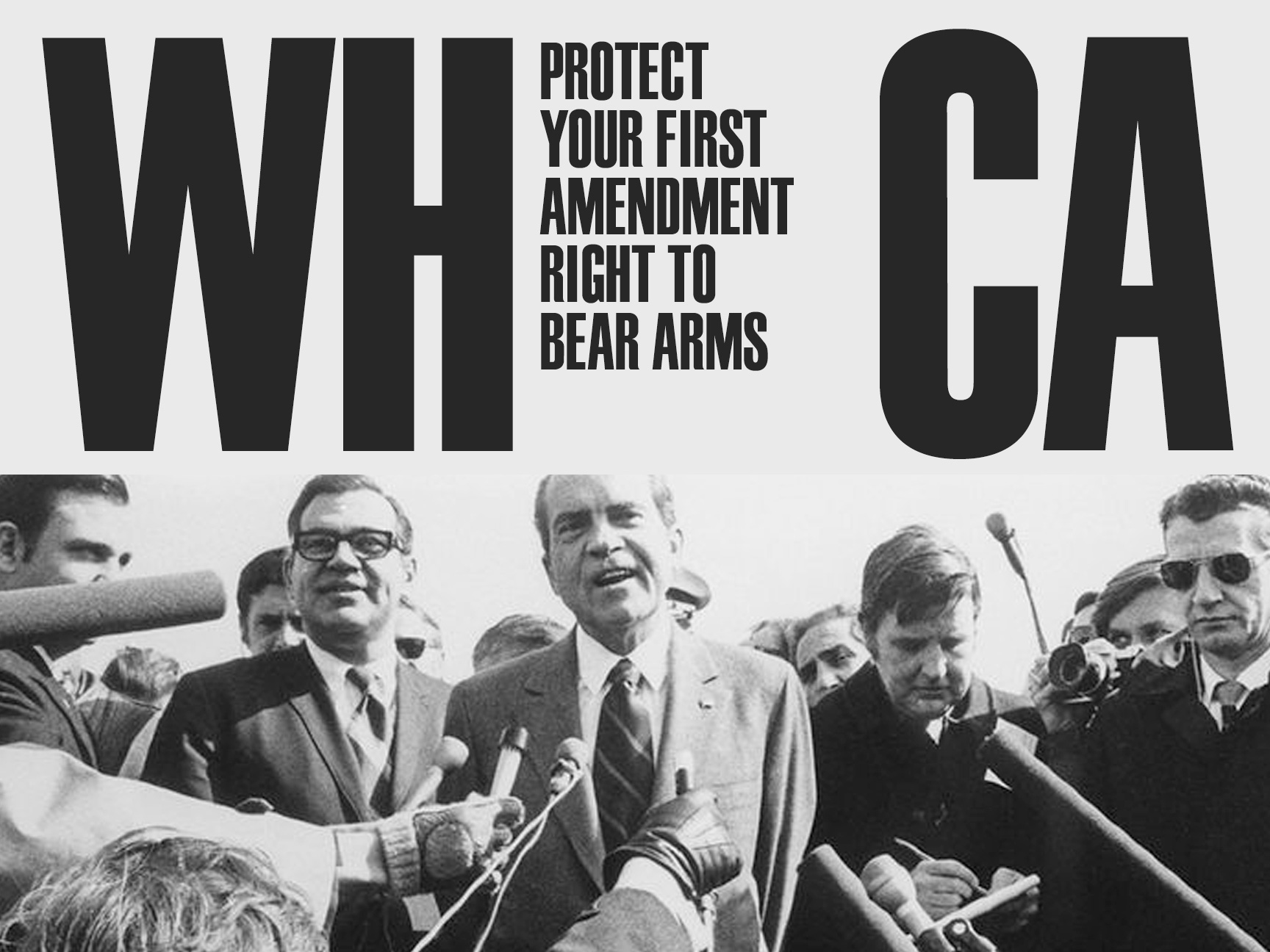

Appeals during any presidency will generally have to be made to their supporters, who are the most likely to forgive certain trespasses.

The Obama billboard was a backwards-looking take on how to use the system to address his abuse of the Espionage Act to prosecute whistleblowers.

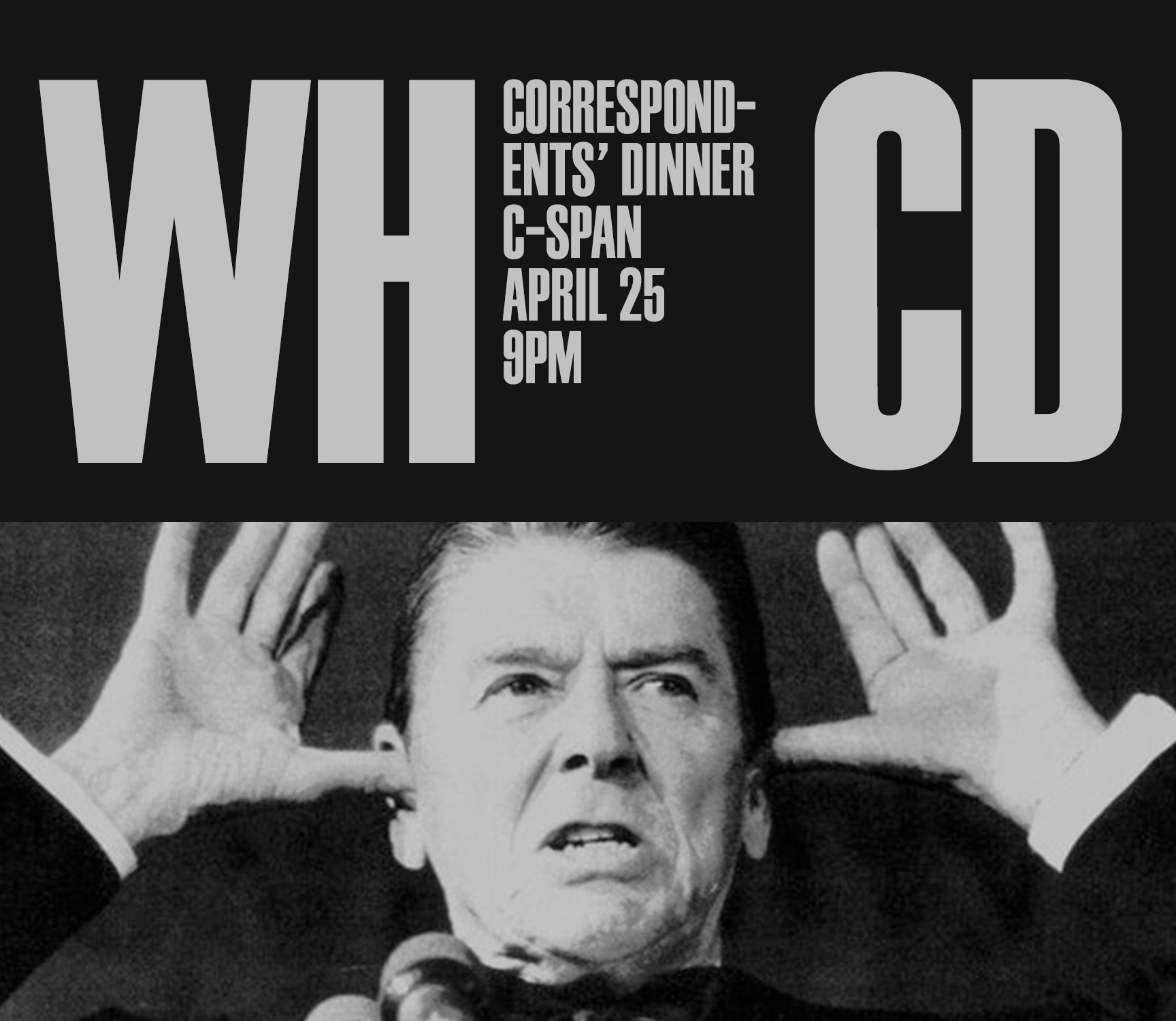

Reagan’s willingness to play along, so to speak, throws shade at Trump, undermining the ‘great-man’ comparisons. The words are his own assessment of himself, from his final WHCD address.

Appeals during any presidency will generally have to be made to their supporters, who are the most likely to forgive certain trespasses.

The Obama billboard was a backwards-looking take on how to use the system to address his abuse of the Espionage Act to prosecute whistleblowers.

Reagan’s willingness to play along, so to speak, throws shade at Trump, undermining the ‘great-man’ comparisons. The words are his own assessment of himself, from his final WHCD address.

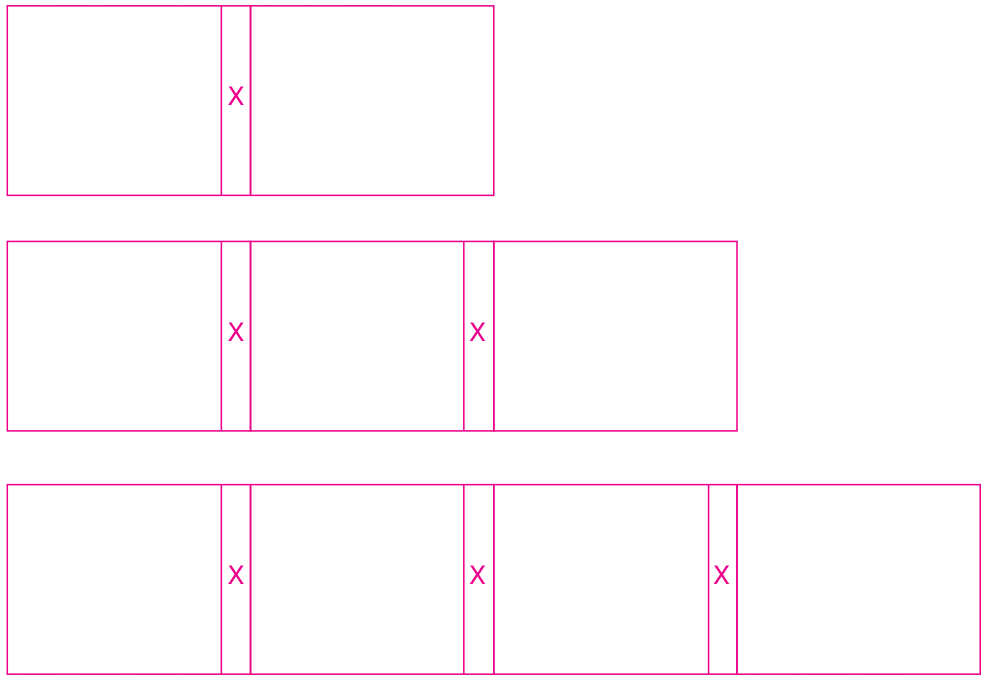

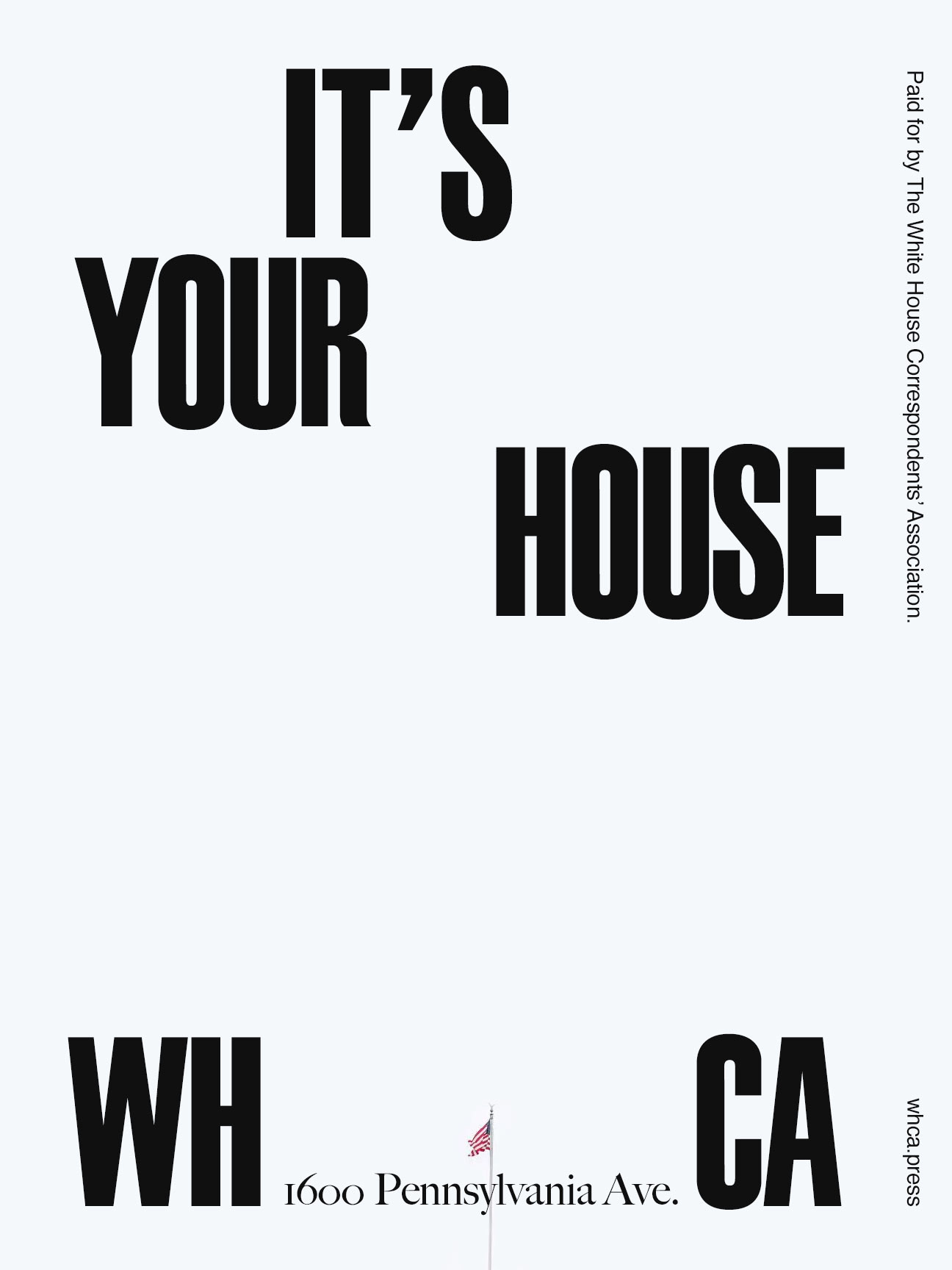

Grid as distance

Physical distance became an essential metaphor for the structural design of the rebrand.

Physical distance became an essential metaphor for the structural design of the rebrand.

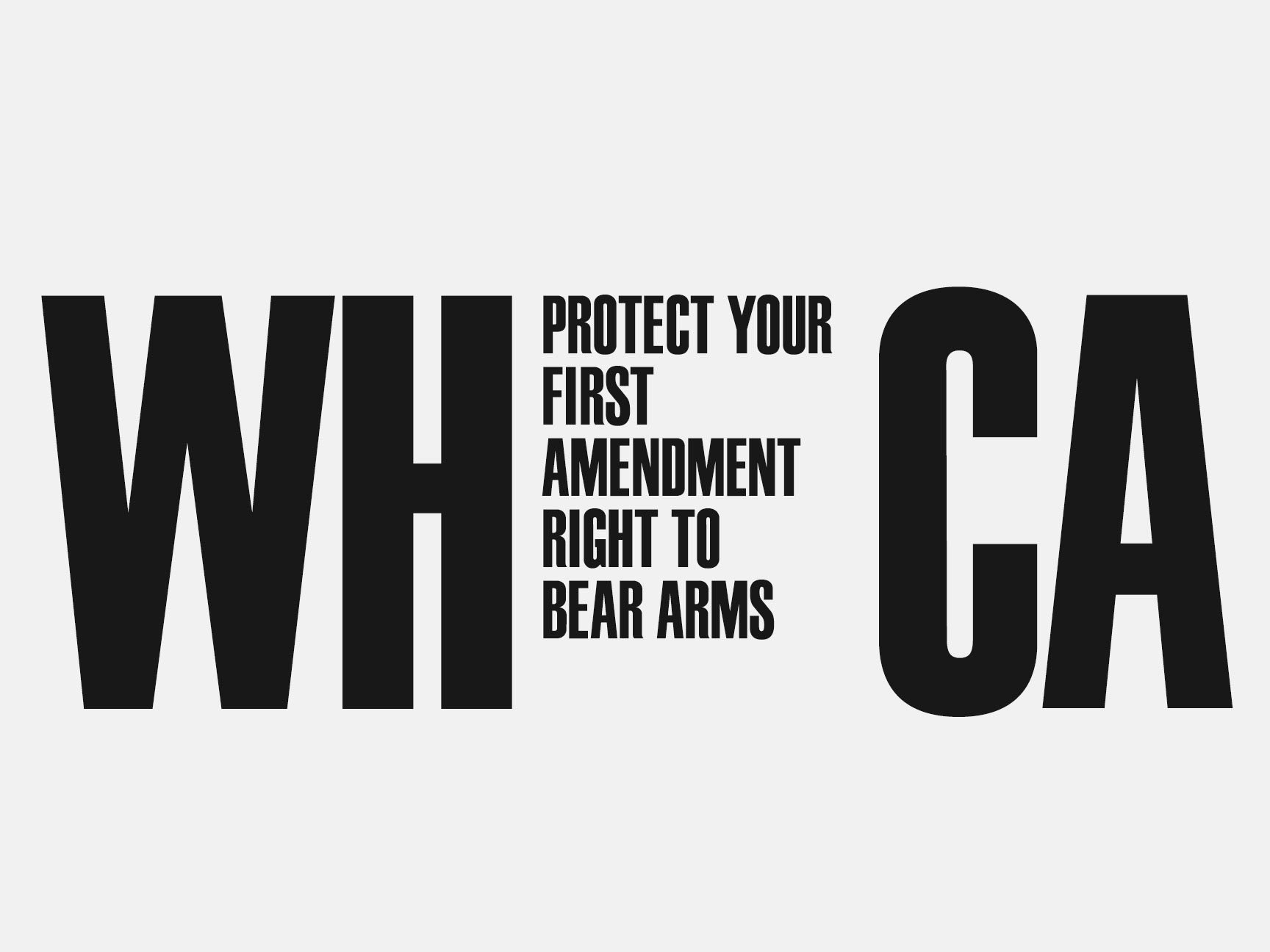

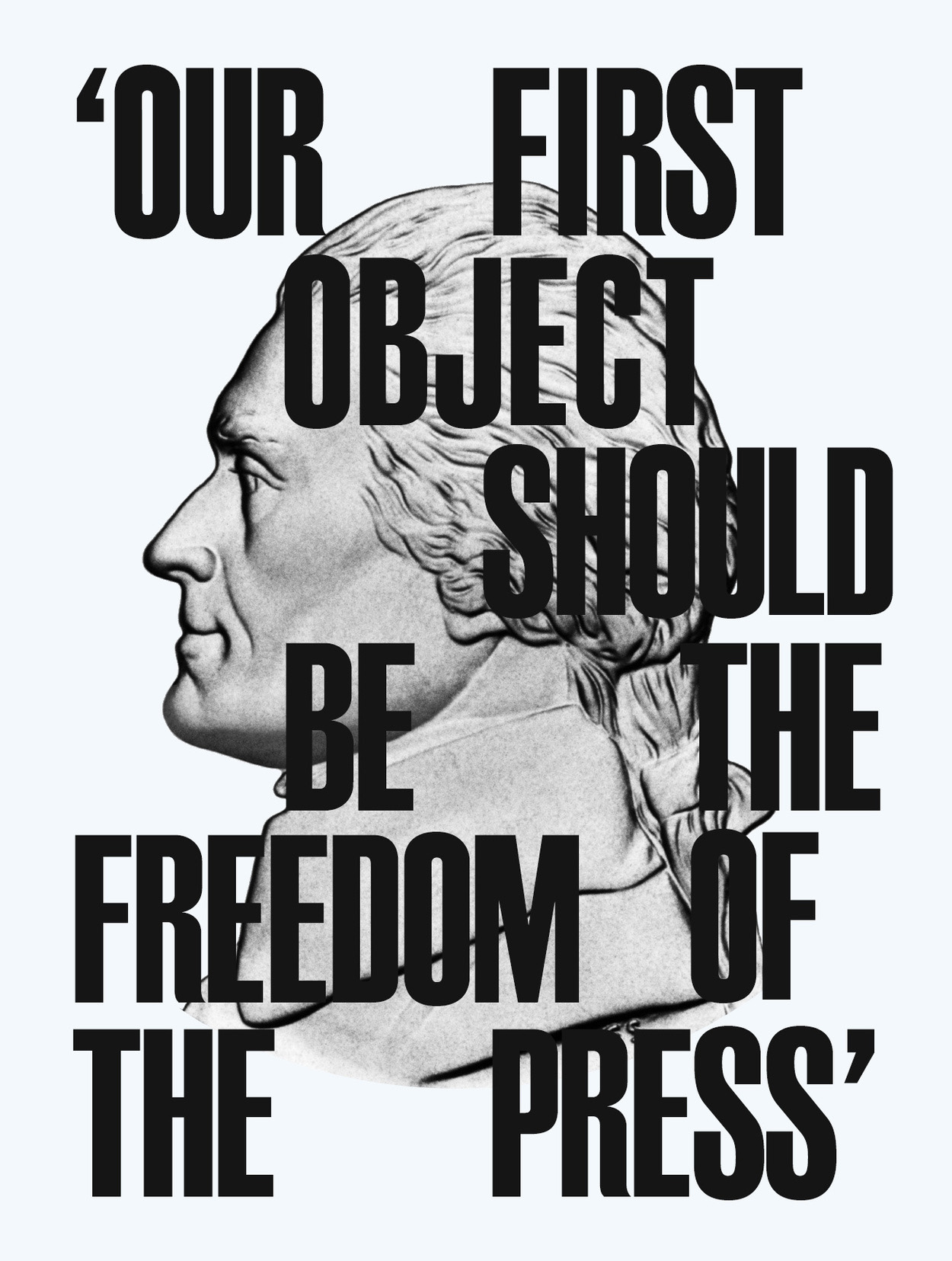

Grid as elision

Posters and ads reference the gaps created by censors’ pens without resorting to cliche blackout marks.

On the right, Jefferson’s obverse is an obscure reference to the use of curreny as propaganda, but more importantly can be read doubly as a remark on the only way to get Trump to take notice: money.

Background

The WHCA story begins with three formative events.

The first came in 1913, when Woodrow Wilson threatened to terminate his press conferences with the informally associated White House press after off-the-record comments found their way into the evening papers. The second, six months later, has it that either the WHCA formed in contrition (account 1: Wilson found the reporters’ questions beneath his intellect and office) or protest (account 2: a rumor leaked that Wilson was cherry picking a more sympathetic press pool). The particulars ultimately matter little, though, as three, these efforts would prove in vain at the sinking of the Lusitania, the event which ostensibly drew us into the war and gave Wilson the pretext to suspend press conferences for good.

The more things change.

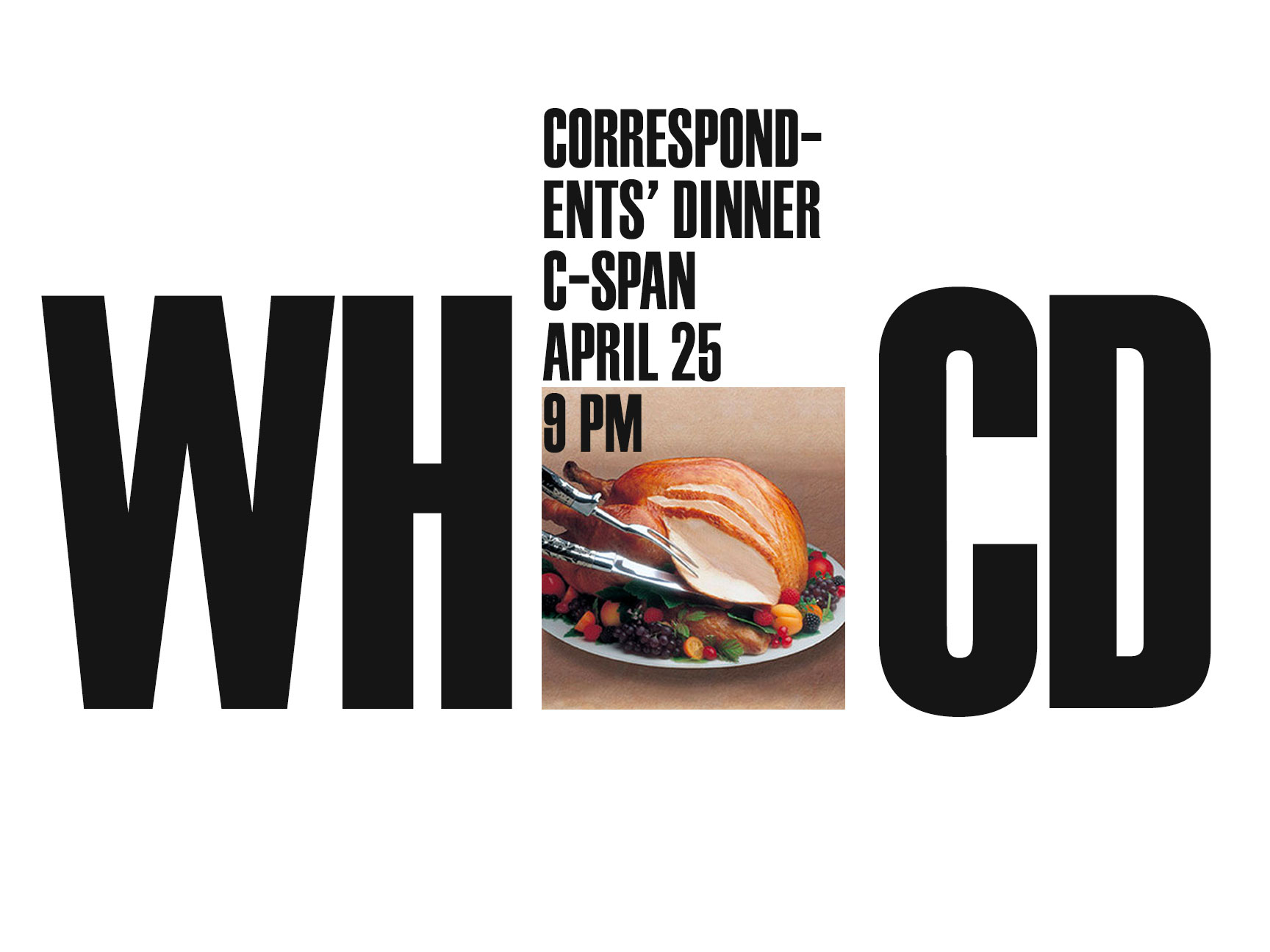

Today the WHCA is known mainly for its annual fundraising dinner, which since 1983 has featured—I probably don’t need to tell you—a roast of the president by a popular comedian. (Say what you will, but remember what Lewis Hyde wrote about social safety valves: “beware the social system that cannot laugh at itself.”) Unfortunately owing to its fun-loving surfeit of spectacle the dinner has won an outsized share of the brand and eclipsed many of the best things about the WHCA; they hoped a new brand and website could help correct some of that imbalance (the dinner does lend itself very well to punchy messaging, and shows off the system quite nicely).

Still, it’s difficult not to make this entirely about Trump. Had he not acceded to power I think it’s pretty likely the WHCA would have carried on with a two-presidents-old website and a logo set in Copperplate. The brand, if it could be called a brand, never spoke the visual language of advocacy, but it never needed to. Trump changed that.

Now with the cameras turned the other way the public needs to realize the WHCA’s work goes well beyond a daily, now occasional, forty minutes of Q&A with the press secretary, into a broad range of activities which support journalism education and professional reporting. But even if the briefing is the public’s only frame of reference, we should remember that what’s played out in that room, Ethel Payne pressing Eisenhower on civil rights issues, for example, has done more to shape the course of national events than Americans know to give it credit. Questions, even unanswered questions, have nation-shaping power.

The first came in 1913, when Woodrow Wilson threatened to terminate his press conferences with the informally associated White House press after off-the-record comments found their way into the evening papers. The second, six months later, has it that either the WHCA formed in contrition (account 1: Wilson found the reporters’ questions beneath his intellect and office) or protest (account 2: a rumor leaked that Wilson was cherry picking a more sympathetic press pool). The particulars ultimately matter little, though, as three, these efforts would prove in vain at the sinking of the Lusitania, the event which ostensibly drew us into the war and gave Wilson the pretext to suspend press conferences for good.

The more things change.

Today the WHCA is known mainly for its annual fundraising dinner, which since 1983 has featured—I probably don’t need to tell you—a roast of the president by a popular comedian. (Say what you will, but remember what Lewis Hyde wrote about social safety valves: “beware the social system that cannot laugh at itself.”) Unfortunately owing to its fun-loving surfeit of spectacle the dinner has won an outsized share of the brand and eclipsed many of the best things about the WHCA; they hoped a new brand and website could help correct some of that imbalance (the dinner does lend itself very well to punchy messaging, and shows off the system quite nicely).

Still, it’s difficult not to make this entirely about Trump. Had he not acceded to power I think it’s pretty likely the WHCA would have carried on with a two-presidents-old website and a logo set in Copperplate. The brand, if it could be called a brand, never spoke the visual language of advocacy, but it never needed to. Trump changed that.

Now with the cameras turned the other way the public needs to realize the WHCA’s work goes well beyond a daily, now occasional, forty minutes of Q&A with the press secretary, into a broad range of activities which support journalism education and professional reporting. But even if the briefing is the public’s only frame of reference, we should remember that what’s played out in that room, Ethel Payne pressing Eisenhower on civil rights issues, for example, has done more to shape the course of national events than Americans know to give it credit. Questions, even unanswered questions, have nation-shaping power.

Interactive and display advertising

Transportation and infrastructure are key to circulation and repetition.

The Brexit bus was successful in a way that typical mobile propaganda was not, partly because political advertising there, as here, is not regulated the same as consumer advertising.

But except for this piece by a semiotician there’s been hardly anything written about the use of the coach in British culture and what impact that may have had on how the message was received.

Transportation and infrastructure are key to circulation and repetition.

The Brexit bus was successful in a way that typical mobile propaganda was not, partly because political advertising there, as here, is not regulated the same as consumer advertising.

But except for this piece by a semiotician there’s been hardly anything written about the use of the coach in British culture and what impact that may have had on how the message was received.

The president v. the people

Fights over the First Amendment rarely played out in popular news. Most liberals would agree that Obama was a man whose deference to the inalienable right to speak one's mind to power was so pure, so true, so limpid, he even patiently, graciously took hecklers' interruptions on sufferance.

The press would tell you a different story.

They did tell us, in fact, about the literal FOIA blackouts, about the threats to prosecute and jail reporters along with government whistleblowers, about the unlawful search and seizure of their phone records. These were arguably as inimical to the First Amendment (and the Fourth) as anything Trump has done so far.

But it’s a problem congenital to the office. Returning to Woodrow Wilson, the Espionage Act Obama and Holder invoked to prosecute whistleblowers was partly authored by Wilson and pushed through Congress as a means of suppressing opposition to Wilson’s hawkish about-face upon entering the first World War. Still not quite satisified with this overreach he added the Sedition Act in 1918, which forbidding outspoken opposition led to a handful of prosecutions, no press—a bridge too far, perhaps—but union leaders, most famously the socialist Eugene Debs, didn’t fare as well.

The problem of the press still nettled Wilson, however. Denied a request to Congress for executive censorship authority, he realized he could needle newspapers to death with propaganda, establishing an ‘information’ office and burying them in so many press releases that journalists couldn’t keep up with reader demands. This shrewdly allowed the writers of his chief propagandist, George Creel, to step “into the resulting vacuum and provide a vast number of official stories that looked like news.” (Think sponsored content, without the sponsored content disclaimer.)

This is germane to this case study for a couple reasons. One, going back to the brand narrative, we see how censorship acts as a displacing force, for example, making space for the appearance of but not the substance of truth, driving a wedge between journalists and their work, creating verisimilitude.

I prefer ‘displacing’ to ‘distorting’ when talking about propaganda. Distortion renders something at least partly unreadable, and illegibility invites interpretation.

However, if we think of the truth as a picture expanding infinitely out of its frame, connecting an overlapping network of events, then what organized propaganda does is find a part of the picture most coherent with its version of events and shifts the frame to include it. (The best example I know of this in America is the explanation invented years later to excuse the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as necessary to prevent the loss of a million or more marines. The original reason, delivered by Truman, was to demonstrate the might of American scientific progress and as a warning to non-democratic governments. After a piece in the New Yorker detailed the aftermath and humanized the Japanese people Americans started to doubt nuclear inevitability as policy. Mac Bundy, author of the lie, re-shifted the narrative frame back to GIs by ghost writing an op-ed for Harper’s, an equally erudite magazine.)

This is also to underscore the cumulative effects on our rights. Until Congress votes to rescind them the acts mentioned exist on the books to seduce future presidents into taking advantage of their precedent.

Trump has hinted to all of these.

The press would tell you a different story.

They did tell us, in fact, about the literal FOIA blackouts, about the threats to prosecute and jail reporters along with government whistleblowers, about the unlawful search and seizure of their phone records. These were arguably as inimical to the First Amendment (and the Fourth) as anything Trump has done so far.

But it’s a problem congenital to the office. Returning to Woodrow Wilson, the Espionage Act Obama and Holder invoked to prosecute whistleblowers was partly authored by Wilson and pushed through Congress as a means of suppressing opposition to Wilson’s hawkish about-face upon entering the first World War. Still not quite satisified with this overreach he added the Sedition Act in 1918, which forbidding outspoken opposition led to a handful of prosecutions, no press—a bridge too far, perhaps—but union leaders, most famously the socialist Eugene Debs, didn’t fare as well.

The problem of the press still nettled Wilson, however. Denied a request to Congress for executive censorship authority, he realized he could needle newspapers to death with propaganda, establishing an ‘information’ office and burying them in so many press releases that journalists couldn’t keep up with reader demands. This shrewdly allowed the writers of his chief propagandist, George Creel, to step “into the resulting vacuum and provide a vast number of official stories that looked like news.” (Think sponsored content, without the sponsored content disclaimer.)

This is germane to this case study for a couple reasons. One, going back to the brand narrative, we see how censorship acts as a displacing force, for example, making space for the appearance of but not the substance of truth, driving a wedge between journalists and their work, creating verisimilitude.

I prefer ‘displacing’ to ‘distorting’ when talking about propaganda. Distortion renders something at least partly unreadable, and illegibility invites interpretation.

However, if we think of the truth as a picture expanding infinitely out of its frame, connecting an overlapping network of events, then what organized propaganda does is find a part of the picture most coherent with its version of events and shifts the frame to include it. (The best example I know of this in America is the explanation invented years later to excuse the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as necessary to prevent the loss of a million or more marines. The original reason, delivered by Truman, was to demonstrate the might of American scientific progress and as a warning to non-democratic governments. After a piece in the New Yorker detailed the aftermath and humanized the Japanese people Americans started to doubt nuclear inevitability as policy. Mac Bundy, author of the lie, re-shifted the narrative frame back to GIs by ghost writing an op-ed for Harper’s, an equally erudite magazine.)

This is also to underscore the cumulative effects on our rights. Until Congress votes to rescind them the acts mentioned exist on the books to seduce future presidents into taking advantage of their precedent.

Trump has hinted to all of these.

Reclaiming the narrative

“When [Trump] politely declines an invitation to the WHCD and immediately mounts a Twitter offensive against the ‘dishonest and corrupt fake news media,’ weaponize popular Republican nostalgia against him.”

“When [Trump] politely declines an invitation to the WHCD and immediately mounts a Twitter offensive against the ‘dishonest and corrupt fake news media,’ weaponize popular Republican nostalgia against him.”

Narrative framework

The earlier use of ‘organized’ in the context of political propaganda might seem to disqualify Trump, who seems totally chaotic by these lights. But as the linguist George Lakoff pointed out in a 2018 Guardian op-ed, Trump is, despite appearances, “winning the linguistic war.”

Consider his use of paltering—“the devious art of lying by telling the truth,” as the BBC puts it. Paltering is when Trump takes a Thomas Jefferson passage out of its larger context and uses it to foment opposition to unfettered expression. Or when he invokes Ronald Reagan to shore up base support for his border wall. Or the two or three examples of the last hour. As Jonathan Swift said of someone of his own time, “the superiority of his genius consists in nothing else but an inexhaustible fund of political lies, which he plentifully distributes every minute that he speaks.” But it's genius nonetheless.

By contrasting these left and right examples, I hoped to establish a communications framework flexible enough to create a variety of both reactive and proactive counterpropaganda messages.

I suppose calling counterpropaganda proactive would be a contradiction in terms if the same issues didn’t reappear throughout history wherever the people have at least some nominal say on the course of government. Relatively little has changed since Augustus deployed similar methods to con the Roman people into making their free republic into a dictatorship. If that hereditary aversion indeed exists, then advocates like the WHCA should give more weight, even in ‘peacetime’, to sustained counter-narratives—so-called awareness campaigns—that make it more difficult to disarm, desensitize, and thereby disadvantage the general public.

The immediate question is what to do about this war on the press.

It’s a sloppy war, but all that slop is kind of the point. Taking Trump head on is self-defeating, because any tit-for-tat only gives him additional incentive to reinforce his own narrative schemes—to double down, as they say.

Which is to say he needs the free press to tell on him: “Trump has done this with such longevity that bad publicity somehow has become a facet of his perceived authenticity,” wrote Michael Kruse for Politico Magazine, back in July 2016. “He has done it with such consistency that a lack of bad publicity weirdly would feel like a betrayal to his brand.” Even most denials are done sort of sous rature, like a shrug, never completely erased but jumbled together, bad, worse or worst, into some horrible, undecidable mythic canon.

So—meet odd manners with odd angles. When he politely declines an invitation to the WHCD and immediately mounts a Twitter offensive against the “dishonest and corrupt fake news media,” weaponize popular Republican nostalgia against him. When he manipulates the correspondence of a Founding Father to weaken the historical legitimacy of a free press, let that Founding Father dispute him. Goad him into the traps laid by counterpropaganda. Reclaim the narrative.

(Obama is a different sort of propagandist. I feel bad, as a liberal, besmirching him this way, but there's no other way I can think to characterize his image machine's ability to manipulate the truth. Looking back, I think, unlike Trump, he should have been met fiercely and in the open.)

Consider his use of paltering—“the devious art of lying by telling the truth,” as the BBC puts it. Paltering is when Trump takes a Thomas Jefferson passage out of its larger context and uses it to foment opposition to unfettered expression. Or when he invokes Ronald Reagan to shore up base support for his border wall. Or the two or three examples of the last hour. As Jonathan Swift said of someone of his own time, “the superiority of his genius consists in nothing else but an inexhaustible fund of political lies, which he plentifully distributes every minute that he speaks.” But it's genius nonetheless.

By contrasting these left and right examples, I hoped to establish a communications framework flexible enough to create a variety of both reactive and proactive counterpropaganda messages.

I suppose calling counterpropaganda proactive would be a contradiction in terms if the same issues didn’t reappear throughout history wherever the people have at least some nominal say on the course of government. Relatively little has changed since Augustus deployed similar methods to con the Roman people into making their free republic into a dictatorship. If that hereditary aversion indeed exists, then advocates like the WHCA should give more weight, even in ‘peacetime’, to sustained counter-narratives—so-called awareness campaigns—that make it more difficult to disarm, desensitize, and thereby disadvantage the general public.

The immediate question is what to do about this war on the press.

It’s a sloppy war, but all that slop is kind of the point. Taking Trump head on is self-defeating, because any tit-for-tat only gives him additional incentive to reinforce his own narrative schemes—to double down, as they say.

Which is to say he needs the free press to tell on him: “Trump has done this with such longevity that bad publicity somehow has become a facet of his perceived authenticity,” wrote Michael Kruse for Politico Magazine, back in July 2016. “He has done it with such consistency that a lack of bad publicity weirdly would feel like a betrayal to his brand.” Even most denials are done sort of sous rature, like a shrug, never completely erased but jumbled together, bad, worse or worst, into some horrible, undecidable mythic canon.

So—meet odd manners with odd angles. When he politely declines an invitation to the WHCD and immediately mounts a Twitter offensive against the “dishonest and corrupt fake news media,” weaponize popular Republican nostalgia against him. When he manipulates the correspondence of a Founding Father to weaken the historical legitimacy of a free press, let that Founding Father dispute him. Goad him into the traps laid by counterpropaganda. Reclaim the narrative.

(Obama is a different sort of propagandist. I feel bad, as a liberal, besmirching him this way, but there's no other way I can think to characterize his image machine's ability to manipulate the truth. Looking back, I think, unlike Trump, he should have been met fiercely and in the open.)

Inspiration and origins

The White House press corps has West Wing accommodations. In the American imagination this is as good as saying the White House, though they’re separated from the actual ‘House’ by a short covered walkway and billeted partly underground in a few tiny rooms with low ceilings. The actual briefing room is FDR’s old indoor swimming pool, drained and converted into press offices by Nixon under the pretext of magnanimously providing the press with their own space, though it’s any wonder he didn’t want them wandering his halls anymore.

Today the offices are so spartan, claustrophobic, and dirty the press mainly cabs back to their workaday offices to type up their beat. The WHCA physical address where the executive director sits is actually Watergate.

This got me thinking about how I might represent that physical separation. The idea to use the letters as a symmetrical frame actually came from a laundry truck I used to see on Houston Street in the East Village. Its vinyl logo had peeled away from its front bumper and the four remaining letters I thought framed the license plate in a nice looking way. Chance and the prepared mind, etc.

The tension created in the spacing also resolved how to handle the visual language of censorship, which I wanted to reference without resorting to cliche. While obvious can be useful—sometimes a blunt instrument is exactly what you need—I think a good acid test for an idea is how many stock photos exist of it already. (What truly killed it for me was the surfeit of cloyingly sentimental, dada-lite blackout poetry.)

What’s left unobscured in a FOIA document is generally too anodyne to be of interest or is missing the context that would give it any real meaning. In this view censorship can be seen a matter of distance, in an almost physical sense—to push phrases and sentences apart, to push people away from the truth—and it occurred to me this could be evoked simply by pushing the text apart.

![]()

![]()

![]()

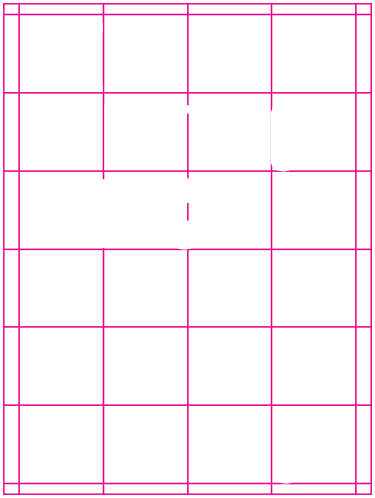

The inspiration to use the grid as a randomizing element came from an Ellsworth Kelly I used to visit in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

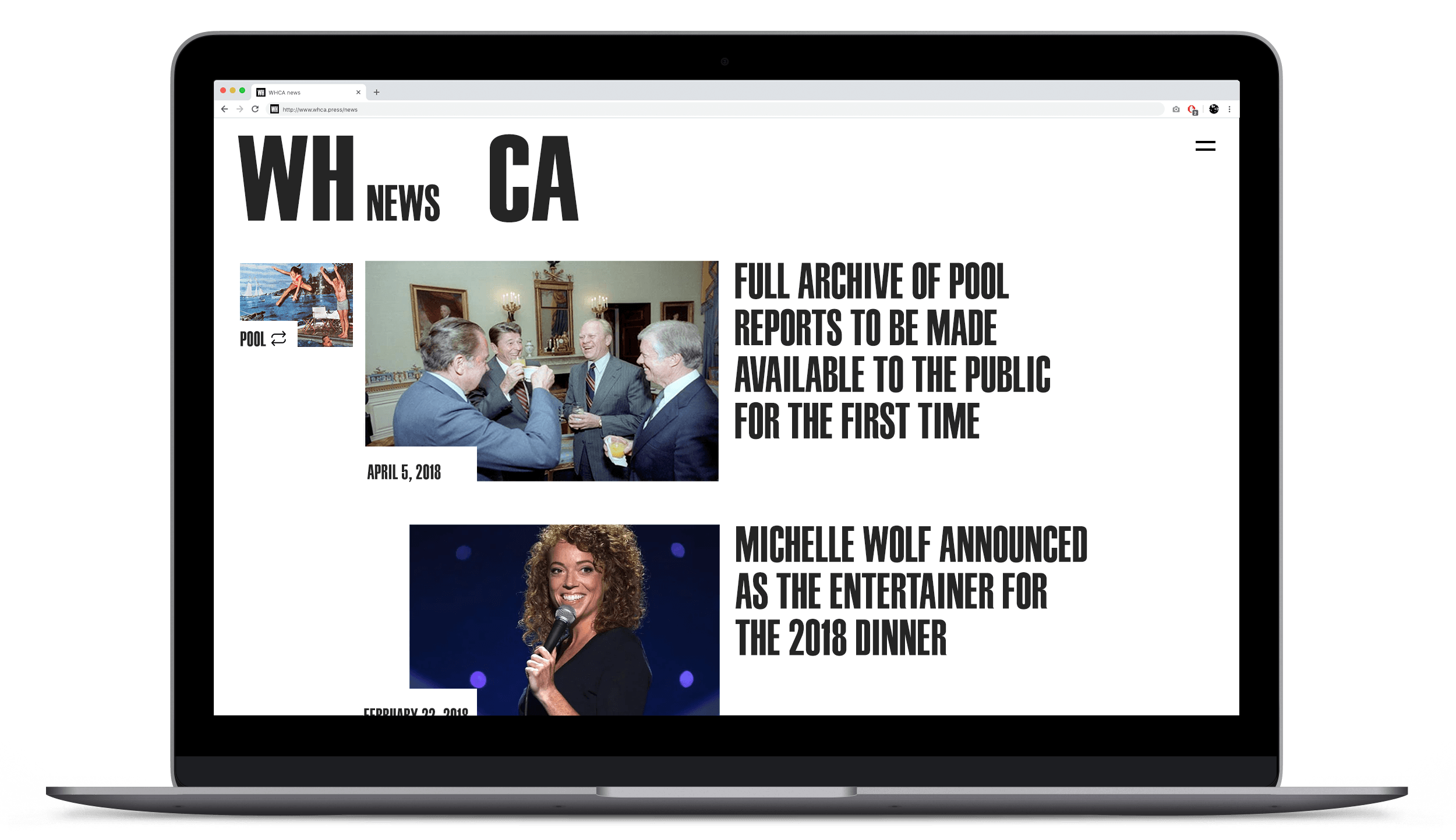

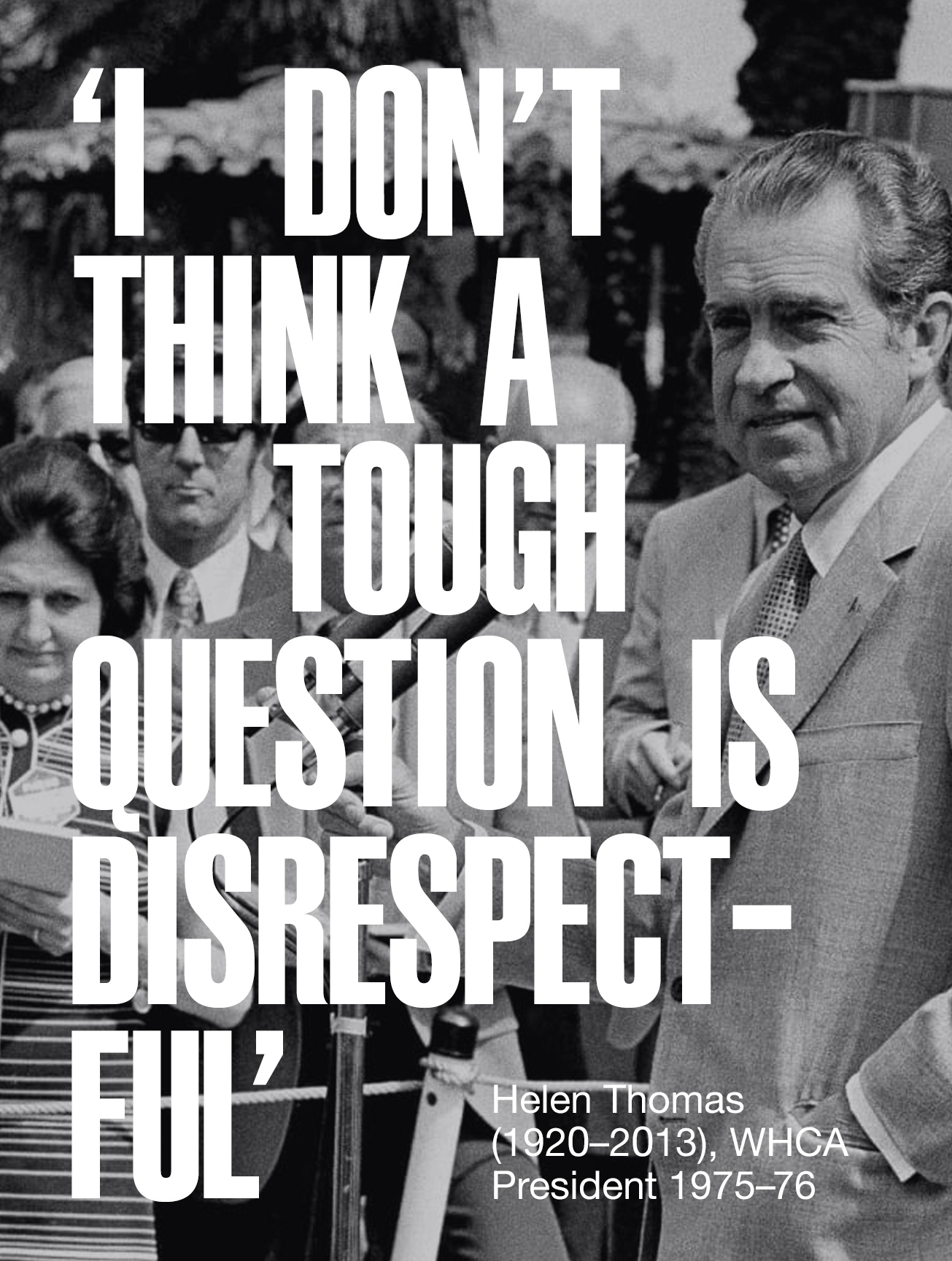

The primary headline text is Schmalfette Grotesk/Haettenschweiler, made popular by Twen magazine. (Druk, above, didn’t go over so hot, and was too unreadable apart from the logotype.) The condensed text was meant to evoke the visual language of news and protest posters while making a reference to the crowded confines of the briefing room and press accommodations.

Photos were predominantly historic to reinforce the organization’s long history covering the White House.

Today the offices are so spartan, claustrophobic, and dirty the press mainly cabs back to their workaday offices to type up their beat. The WHCA physical address where the executive director sits is actually Watergate.

This got me thinking about how I might represent that physical separation. The idea to use the letters as a symmetrical frame actually came from a laundry truck I used to see on Houston Street in the East Village. Its vinyl logo had peeled away from its front bumper and the four remaining letters I thought framed the license plate in a nice looking way. Chance and the prepared mind, etc.

The tension created in the spacing also resolved how to handle the visual language of censorship, which I wanted to reference without resorting to cliche. While obvious can be useful—sometimes a blunt instrument is exactly what you need—I think a good acid test for an idea is how many stock photos exist of it already. (What truly killed it for me was the surfeit of cloyingly sentimental, dada-lite blackout poetry.)

What’s left unobscured in a FOIA document is generally too anodyne to be of interest or is missing the context that would give it any real meaning. In this view censorship can be seen a matter of distance, in an almost physical sense—to push phrases and sentences apart, to push people away from the truth—and it occurred to me this could be evoked simply by pushing the text apart.

Some of this concept’s initial takes, using Druk and Larsseit, 9/17.

The inspiration to use the grid as a randomizing element came from an Ellsworth Kelly I used to visit in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The primary headline text is Schmalfette Grotesk/Haettenschweiler, made popular by Twen magazine. (Druk, above, didn’t go over so hot, and was too unreadable apart from the logotype.) The condensed text was meant to evoke the visual language of news and protest posters while making a reference to the crowded confines of the briefing room and press accommodations.

Photos were predominantly historic to reinforce the organization’s long history covering the White House.